The dream of Star Trek’s Enterprise replicator—or at least my dream of printing my own Lego pieces—is a tiny bit closer to reality thanks to the Form 4, the latest version of Formlabs’ popular compact 3D printer. The Form 4, which starts at $4,500 and is available today, promises to print objects up to five times faster than the previous generation (depending on the material). And perhaps more importantly, the company claims that the Form 4-printed parts’ quality is “indistinguishable from injection molding.” This speed and quality combo pushes us close to the holy grail of 3D printing: the ability to produce high quality objects without ever leaving your desk.

Clik here to view.

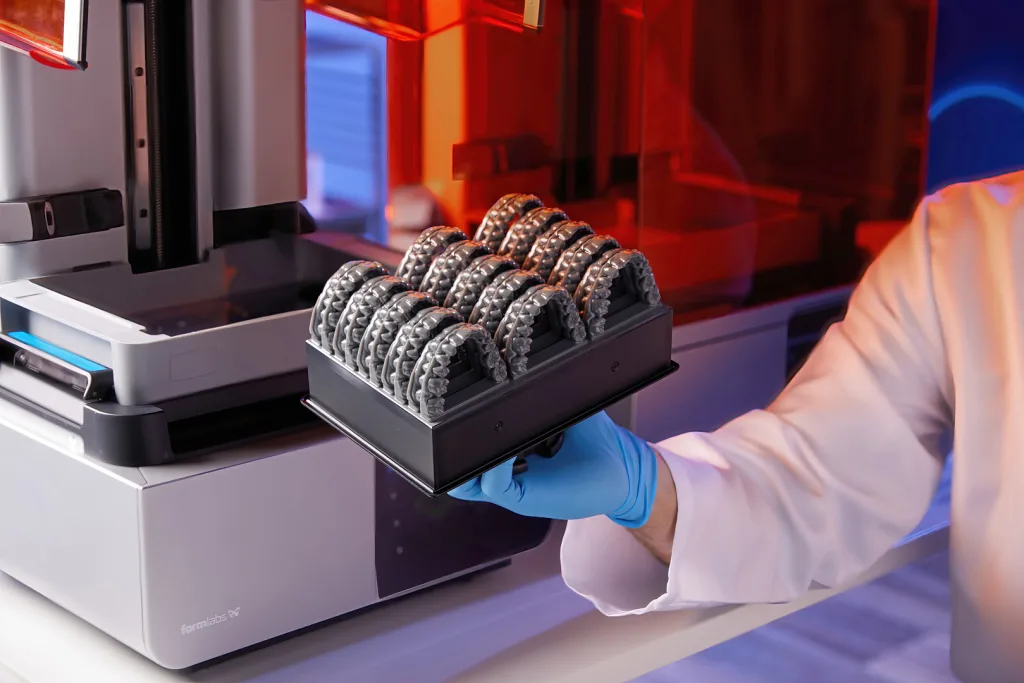

Increased speed and accuracy will deeply affect the workflows of people who use 3D printers on the regular: people like professional designers in automotive, aerospace, consumer goods, and entertainment industries, as well as healthcare professionals who need to make biocompatible custom parts for their patients. “Where on the Form 3 most jobs would take about a workday, now we can run two or three iterations of a given print in one workday,” says Cole Durbin, Formlabs’ Technical Program Manager.

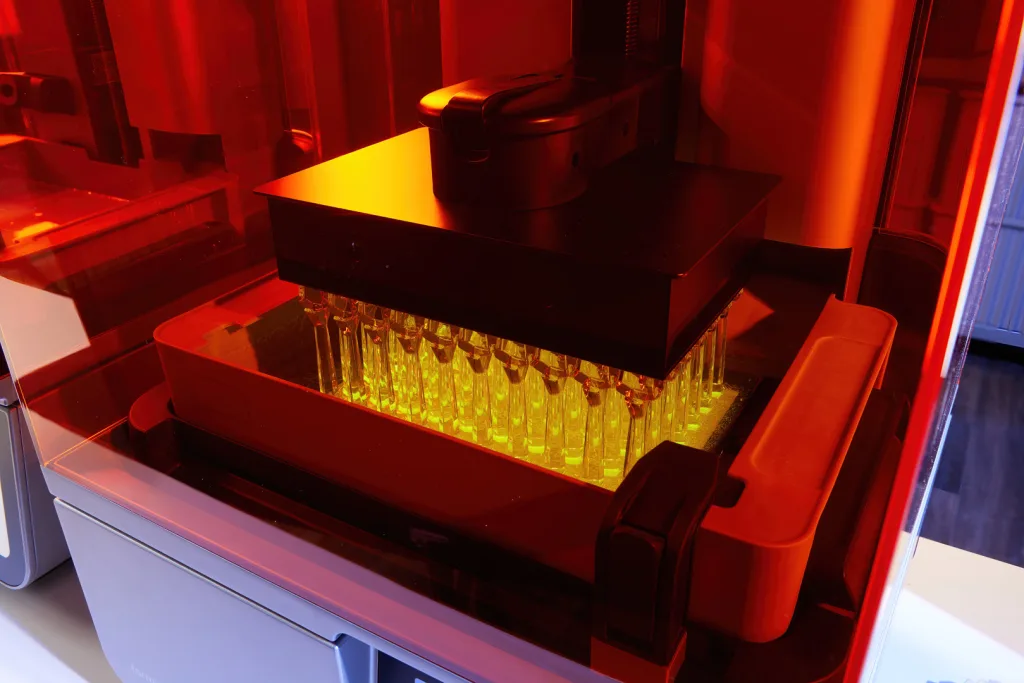

Durbin says there are material efficiencies gained with the new printer. Dentists, for example, will be able to print 130 dental crowns in just 20 minutes. For designers, producing multiple iterations in a single day will help them experiment more quickly and cut down development time. Durbin should know: Formlabs ate its own dog food, prototyping many of the Form 4 parts over the past four years using its own technology.

Clik here to view.

Hot design challenge

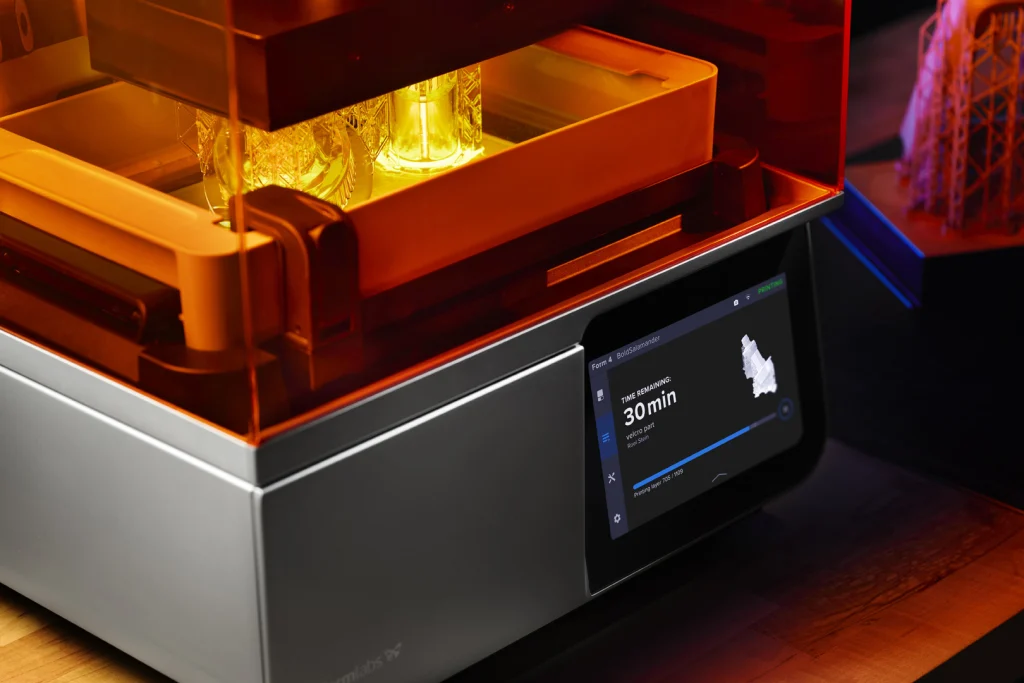

Powering the Form 4’s performance is something called the Low Force Display (LFD) print engine, which helps to cure each layer of material in a 3D-printed object. Durbin explains that his team developed the LFD in-house to reduce the force applied during the printing process and increase speed of production.

Clik here to view.

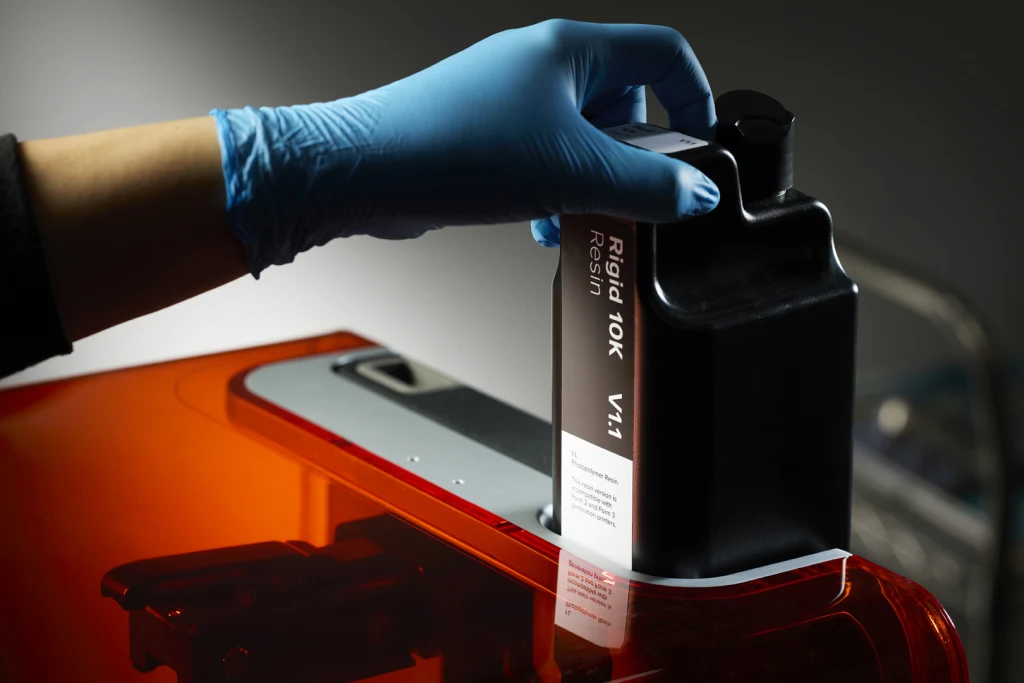

Printing in the countertop microwave oven-size Form 4 begins with the user filling up the tank with a liquid chemical that will cure—or “solidify”—to form the final object. This liquid will be different depending on the final piece; a dental crown requires a different formulation from, say, a Lego brick. Materials like silicone, ceramic, polyurethane, and basically any chemical substance that is certified for printing by Formlabs—about 40 different materials, according to Durbin—can get you all different properties: more or less flexibility, rigidity, impact resistance, and even flame retardancy.

Clik here to view.

Durbin says the Form 4’s new LED array and LCD screen—which has 50-micron pixels, the average thickness of a human hair—apply a more intense light to the material, resulting in curing that happens two to five times faster than with the previous generation of machine. In very broad terms, these units “flash” a matrix of dots that bind the liquid material one layer at a time. Think about it like slicing cold cuts in reverse: instead of seeing the layers coming out of the slice machine, you are gluing them one after the other until you end up with the entire bologna.

A more efficient machine

To make the machine even more efficient, Durbin and his team had to figure out how to keep the machine from overheating. “Some of the challenges around speed come down to thermals,” he describes. “Basically, when you make a printer like this, lots of these components get very hot and we have to keep them cool.”

Clik here to view.

The printer, Durbin says, has a relatively intricate cooling design. “We have three different fans in the printer that are routing air in relatively complex ways throughout the printer to keep everything cool,” he says. The main fan is dedicated to the most delicate part: the LCD. When LCDs reach high temperatures, they can damage, so Formlabs installed a dedicated fan right on the backlight unit connected to a big heat sink that pulls heat off of those LEDs to keep it cool.

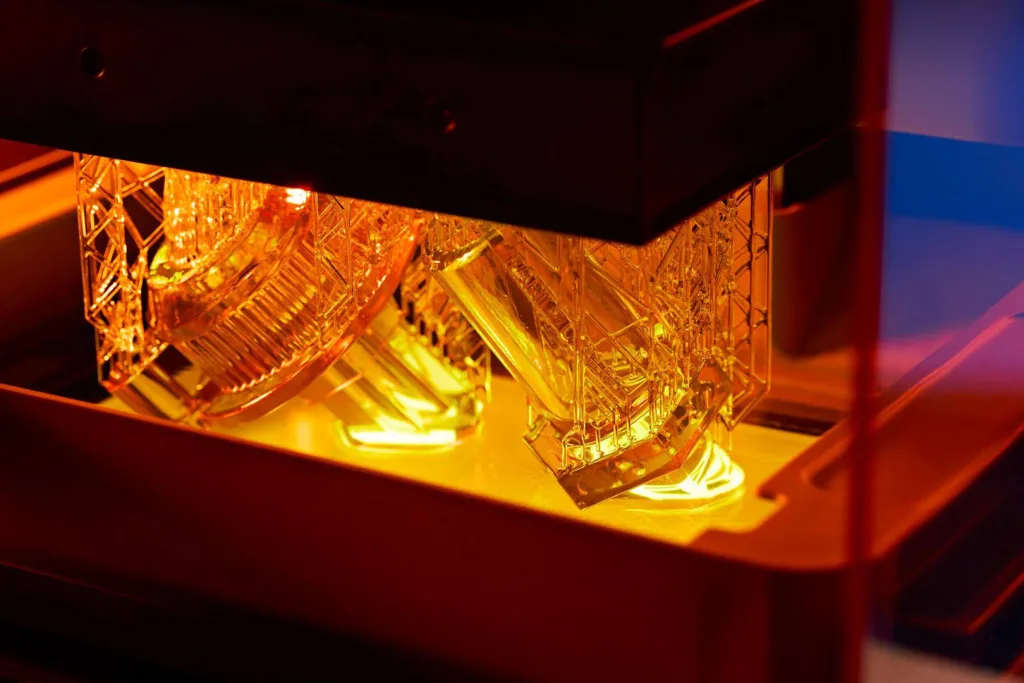

Release film sits on top of the light print unit, ensuring the printer works quickly and remains cool. Durbin explains that this part is designed to help the machine’s tank film freely peel away every layer as it prints. The film allows the machine to lay down another layer of the 3D object, increasing print speed. “[It] basically allows air to come in underneath that tank film and freely lift off, so that we can print quickly, but also with very low force, which is a really important thing,” Durbin says.

Clik here to view.

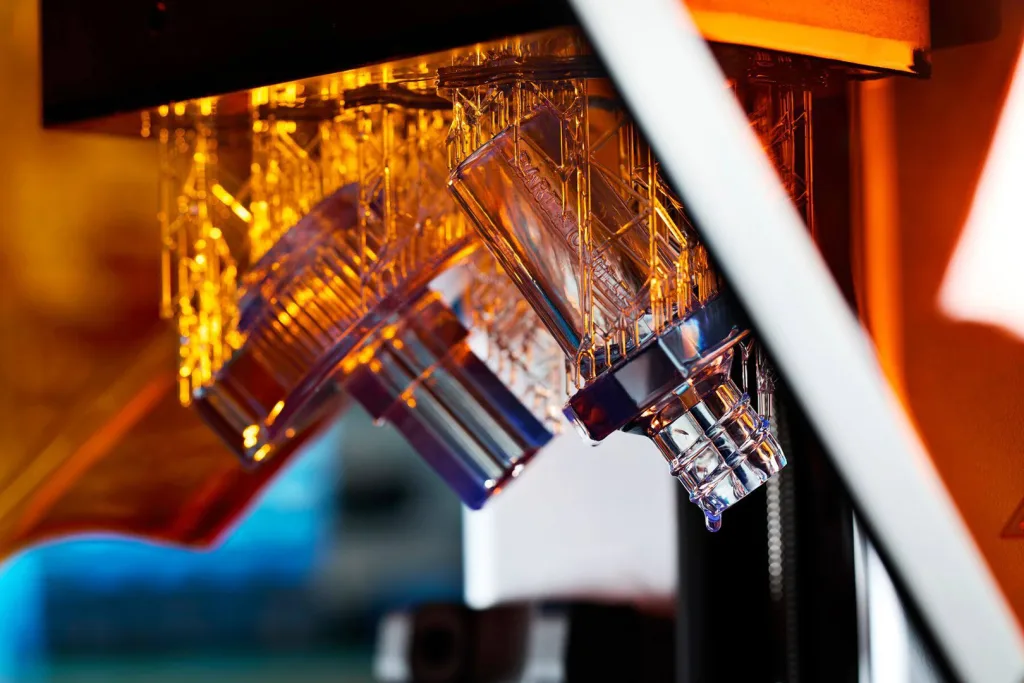

The company claims that, unlike many competitors, this low force design reduces the physical stress on the part. Since the film allows for easy peeling, it doesn’t have to exert a lot of force to separate the printing unit from the object being printed. This delicate process helps maintain the integrity of the print, which in turns allows for increased accuracy and better surface finish. The goal is for the 3D-printed object to be on par with traditional manufacturing methods like injection molding. And because there’s less stress, you can also print with fewer supports—the little pillars that keep a 3D-printed object from falling apart during the printing process.

“The secret of SLA printing is once the part comes off, you still have to remove it from supports and post-process it,” Durbin says. You have to wash it. You sometimes have to cure it again. And printing with fewer, more easily removable supports is critical to getting the best end result, and faster. With the Form 4, Durbin claims that the support’s connections are so few and so thin that, for most parts, you can carelessly tear them off without fear of breaking the actual printed part. “It is a really nice experience, and is made possible by that release film that is on top of the LPU,” he says.

Clik here to view.

A matter of uptime

Durbin says the custom engineering that keeps all of the printer’s components operating at low stress and cool temperatures helps preserve the hardware’s durability. The company wanted to keep the machine reliably running for longer periods of time to cut down on costs for the users and themselves.

Formlabs says the more reliable the machine is, the less they have to spend on servicing the machine. “Design choices like that take a lot of engineering effort, and they take intentional choice and testing,” Durbin says. “But ultimately, part of reliability is uptime. If your printer has a problem, we want our customers to be able to fix it, ideally themselves, without our assistance. We don’t want to send a field technician or have them send their machine back to us.”

Formlab designed the Form 4 with modules that users can replace by themselves. “[We wanted] to keep the uptime high for [customers’] machines,” Durbin says. “Modular design and letting people swap parts in and out is critical for that.” The Light Processing Unit (LPU) is modular, for example, so when it gets to the end of its life, someone can change it more or less like a Nintendo cartridge.

Durbin says that the resin tank has already been tested with up to 75,000 layers of printing and counting, which is a lot for devices that are subjected to such extreme heat conditions. “We are early in our testing, and we don’t want to over-promise to customers, but we think we have a really robust system.” And for most customers, he says, “the rest of the components will last for the full product life cycle of a printer” without the need to swap.

That’s a bold claim that only time will prove, but it sounds like a big step forward for this technology, and good news for 3D designers everywhere. I just hope that for the rest of us, the end game here is for these printers to fulfill their Star Trek promise and print out not only full bolognas, but entire deli sandwiches.