Jails and prisons are often slow to introduce new technology but thousands of inmates in state institutions across the country are now taking courses on specialized tablets designed for use behind bars, through a unique arrangement with prison tech company JPay.

"We have inmates who are currently earning college credits for the first time ever," says JPay founder and CEO Ryan Shapiro.

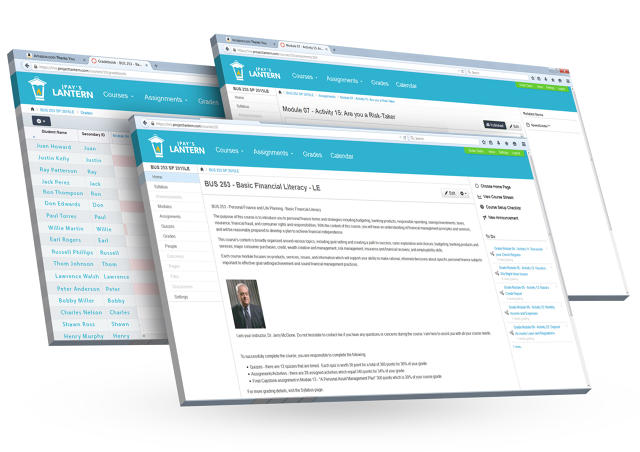

JPay has offered tablets and media players since 2008 that let inmates do things like buy music and games and draft emails to loved ones outside the prison, and the company released a learning management system called Lantern for the devices last fall.

Lantern lets inmates read course material and complete quizzes, papers, and other assignments on JPay's tablets, letting them upload and download course materials and messages to instructors using in-prison kiosk computers, Shapiro says.

About 7,000 students in Ohio, Washington, and Georgia prisons are now studying for their high-school equivalency degrees or taking courses offered by local colleges with the help of the devices, he says.

JPay has come under fire in the past for the fees it charges for its various offerings, including transferring funds to prisoners and various digital services that can be dramatically more expensive than outside of prison—at one Ohio prison, for instance, the company advertises that it charges $9.90 for a 30-minute "video visitation" session with loved ones outside the prison and at least 20 cents per page of inbound or outbound email.

That's different from how prisons handle less high-tech forms of communication, notes Alex Friedmann, the associate director of the Human Rights Defense Center, which has criticized JPay and other prison services companies in the past.

"If you want to send them a letter, you don't have to pay the jail some kind of additional fee to deliver the letter to them," he says, adding that the cost for these new services shouldn't become a burden to inmates and their families. "The cost of our criminal justice system should be borne by everyone just like our public school costs is borne by everyone."

Shapiro says that JPay's new educational material is offered free of charge and tablets are sold "at cost."

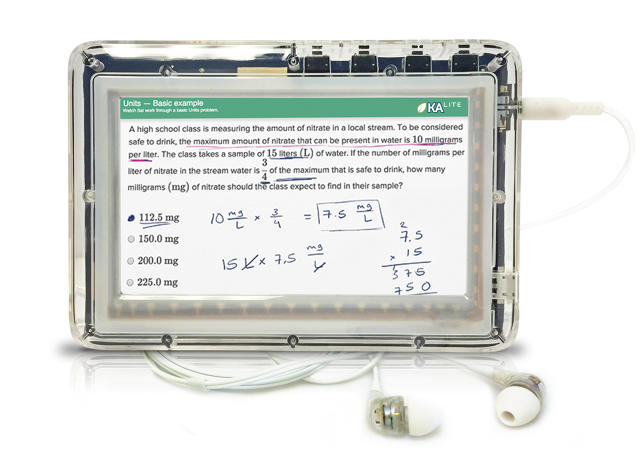

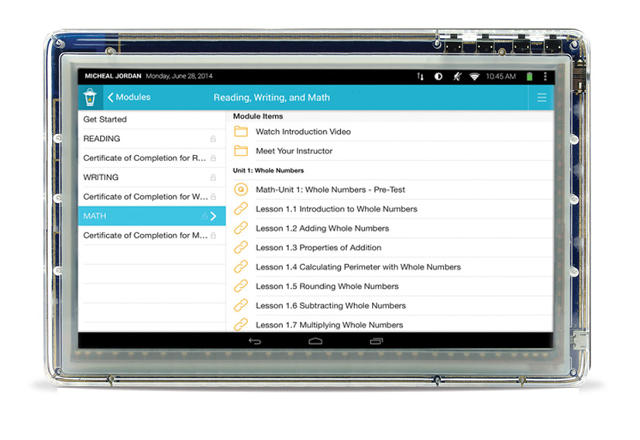

The locked-down tablets, which have transparent plastic bodies for easy inspection and run a custom version of Android, don't have ordinary Internet access and can only install content approved by JPay and prison officials. But the company announced last week that it's now also offering prisoners free access to Khan Academy educational videos through the Foundation for Learning Equality's KA Lite program,which offers access to the materials without an Internet connection.

"In Georgia, we have just eclipsed over 100,000 Khan Academy video downloads," says Buster Evans, the state's assistant commissioner of inmate services. The most popular video so far is an astronomy lesson focusing on the "birth of stars," a subject included in the GED curriculum, he says.

The state plans to use inmate benefit funds, derived from non-taxpayer sources like prison commissary sales, to distribute the tablets to each of Georgia's 37,000 state inmates, he says. The devices also let inmates access a variety of books—some for free and some for pay—and take quizzes to prep for the GED exam, he says.

And in addition to helping inmates study outside of formal classroom programs, which might only run for a couple of hours per day, prison officials have found the tablets help to keep the inmates occupied and well behaved, Evans says.

"The first couple nights after they've gotten their devices, they say it's the quietest it's ever been," he says.

Younger inmates often help older prisoners, who haven't previously been exposed to tablets and smartphones, learn to use the machines, he says.

In other prison systems, inmates or their families can purchase the tablets, generally for about $50 or $60, Shapiro says. So far, the company has distributed about 70,000 of the devices nationwide.

Friedmann points out that educational materials that make prison authorities more likely to buy tablets for inmates ultimately leads to a larger market for JPay's music, email, and other services.

"The customer is actually the corrections agency," he says. "It's not actually the inmates—they're not the ones buying the tablet."

JPay declined to provide any specifics on its own financials, and company spokeswoman Jade Trombetta said in an email that figures reported in a critical 2014 report by the Center for Public Integrity were "inaccurate and inflated." In one document filed as part of a 2014 bid to provide "inmate banking services" to the West Virginia prison system, the company said it expected to process more than $1 billion in funds transfers that year.

Shapiro says the company's always offered money transfer prices at least as favorable as Western Union, and that its systems are more convenient than previous alternatives like delivering cash to prisons to deposit in inmate accounts.

And while the company charges fees for services that can be had essentially for free in the outside world, like email and video conferencing, Shapiro says JPay generally bears the up-front cost of wiring prisons to provide electrical power and network connectivity to its secured kiosk machines and providing the infrastructure to let prison officials review communications.

"I don't know anyone that builds systems, hires people, spends millions of dollars on infrastructure for free," he says.

The virtual "stamps" inmates and their families spend to send email are cheaper than snail mail, and unlike home users who pay a monthly fee to Internet service providers, inmates only pay for the services they use, he says.

"If [critics] looked at our money and looked at our margins, we don't make more money than any other business in the United States," he says.

The revenue from JPay's existing businesses is effectively subsidizing its free educational offerings, Shapiro says.

"We have a very, very big team currently just dedicated to education," he says. "We're talking about a whole, basically, division that doesn't make any money."

Friedmann says he welcomes JPay offering educational resources to inmates but says he'd rather not see them bundled so closely with the company's for-profit services, at least not without stricter regulation of the rates for such services, similar to the price caps the Federal Communications Commission has moved to institute for notoriously pricey prison phone calls.

"Any time you have complete non-regulation and a literally captive audience, which is what you've got in this case, you need some regulation to rein that in," he says.