We take for granted that GPS can get us where we're going pretty much anywhere on earth, but there's one important place satellite navigation systems are essentially guaranteed not to work: under the sea.

The satellite broadcasts that GPS systems rely on can't penetrate very far below the ocean's surface, and that's a problem for unmanned underwater vehicles—essentially, drone submarines—designed to autonomously navigate below the sea.

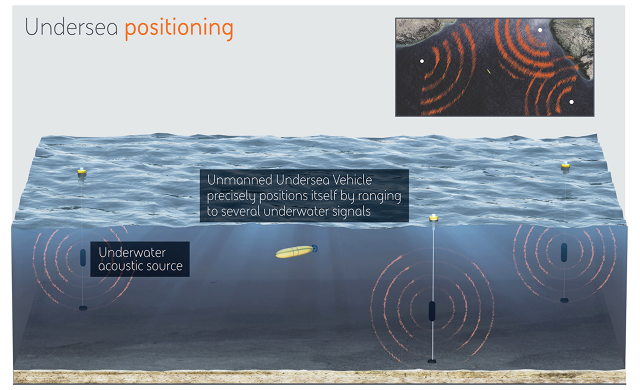

That's why the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has announced plans to build an underwater GPS-style system called Posydon—which stands for Positioning System for Deep Ocean Navigation—that will use underwater sound broadcasts to let submarines determine their own positions without coming to the surface.

Clik here to view.

"By measuring the absolute range to multiple source signals, an undersea platform can obtain continuous, accurate positioning without surfacing for a GPS fix,"the agency says.

So what are the maritime drones used for, anyway? In the past, the U.S. Navy has used these robot subs for clearing underwater mines and for various other underwater reconnaissance missions, but it has plans to deploy them more widely for the purpose of minesweeping, undersea patrols, and other tasks, according to a November report from Bard College's Center for the Study of the Drone.

Surfacing is naturally a particular problem for military missions that require stealth, says Geoff Edelson, director of maritime systems and technology at BAE Systems, a contractor working on the project. And while there are technologies that allow subs to determine their locations to some extent without surfacing, they're often expensive and energy-consuming, which also makes them less than ideal for drone missions.

"For unmanned vehicles, power and energy is at a premium," says Edelson. "If they're using up all their power and energy to navigate, that doesn't really help them in performing their mission."

Essentially, the Posydon system will be a network of underwater sound-emitting devices attached to buoys placed in areas designed to cover wide swaths of the sea. Underwater ships will be able to determine their distance from multiple devices and therefore triangulate their own positions.

"[The devices will be] placed somewhere in the water column at a depth that is good for that part of the ocean," Edelson says. "That's based on the propagation properties of the ocean in those local areas."

The exact signal the devices will transmit has still yet to be developed, but engineers plan to make it resistant to spoofing and jamming for security purposes. Moreover, taking a system based on the straight-line paths of GPS satellite broadcasts and adapting it to underwater sound transmissions—which move a lot more indirectly—will present its own challenges, says Edelson.

"When you put sound in the ocean, it goes over a very complicated, time-variant path," he says. "To be able to understand that and then determine what the actual range was from these very complicated path structures is what makes this problem pretty hard."

The first two phases of the project will involve a mix of real-world tests and computer simulations in order to plan and design the system. Within 30 months, Edelson says, researchers plan to test real-time distance measurements using a single-transmitter system, before moving on to developing a larger prototype with multiple transmitters.

"If these first two phases are very successful, the third phase that DARPA defined would be then a limited deployable system that can really show the positioning capability," he says.

If the system works as well as researchers hope it does, the project could ultimately have applications in the civilian world as well, just as GPS expanded from the defense sector to find itself in billions of smartphones. Existing unmanned subs are already used for underwater oil and gas exploration and other types of underwater surveys and scientific applications. Ultimately, these commercial systems could use a Posydon-type system to hold accurate positions for longer and potentially conduct their own missions more efficiently, Edelson says.

The BAE Systems team, which is working with researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Washington, and the University of Texas, plans to keep the computational requirements of receiver systems low, so they can be used without having to significantly boost the processing power of existing subs.

"You're not gonna have to bring a Cray [supercomputer] onboard, or anything like that," Edelson says.