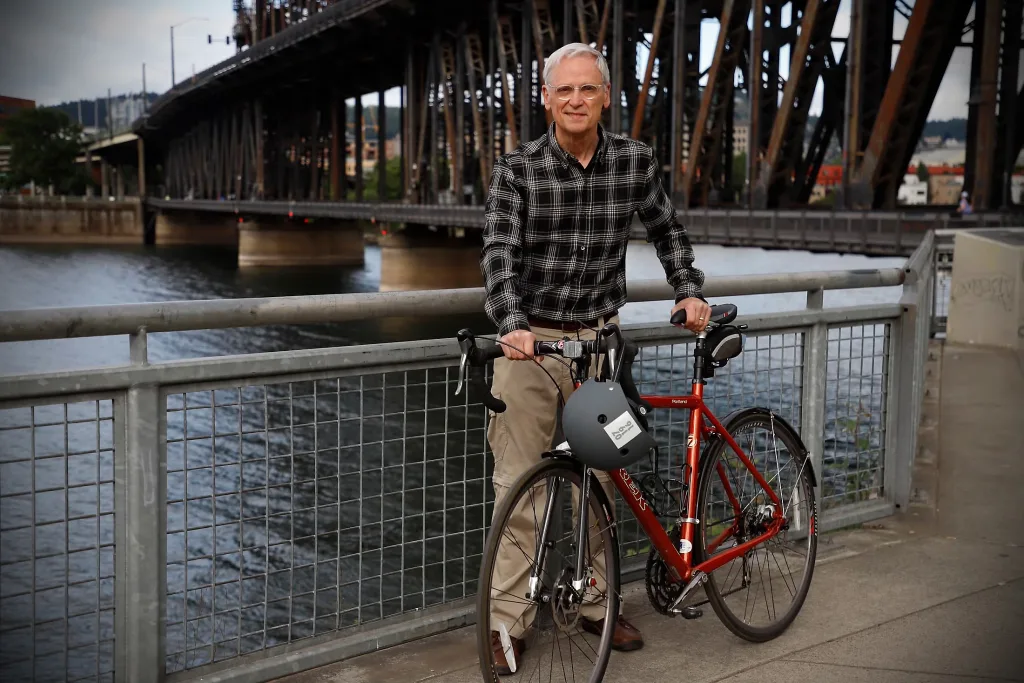

After half a century in Congress, Representative Earl Blumenauer (D-Oregon) has announced he’s retiring at the end of 2024. A cycling enthusiast known for his advocacy on everything from public transportation to cannabis legalization, Blumenauer isn’t leaving the halls of Congress without a final fight. Last month, he introduced legislation that would reinvigorate bicycle manufacturing in the U.S.

In March 1974, Fortune magazine documented the country’s “Bicycle Craze,” citing homegrown manufacturers like Murray and Huffman (Ohio), Schwinn (Chicago), and AMF (Ohio, Arkansas, and Illinois). But after demand fell off in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, brands looked for ways to cut costs and ultimately shifted production to other countries, like China. In 2022, 97.8% of bikes sold in the U.S.—electric and people-powered—were imported. Blumenauer’s Domestic Bicycle Production Act aims to incentivize American companies to make bicycles again through a mix of tariff suspensions, tax credits, and loans. Fast Company spoke to Blumenauer about his first bicycle memory, how bicycles have the power to bridge the political divide, and why America can and should be a powerhouse of bicycle manufacturing once again.

You’ve long been a cycling advocate. What turned you on to cycling, and when?

I remember being 5-years-old and learning to ride a bike. I actually rode a bicycle to school in first and second grades [in Portland]. I’m not a monster cyclist like some. But I’ve enjoyed cycling for recreation purposes and for transportation purposes. Some of my favorite vacations were peddling. I continue to walk or bike to work every day.

What’s your commute like in D.C., where you are right now?

It’s nothing! I live less than a mile away [from the Capitol]. It saved time and money not bringing the car back here.

Has it gotten safer in recent years as D.C. has improved its cycling infrastructure?

Yes. That’s one of the things I’m most proud of: being part of developing the bike infrastructure on Capitol Hill. I led the charge to put bike lanes down Pennsylvania Avenue. It was a really terrific addition to the city landscape. But putting a bike lane down the middle of one of the most well-known streets in America also had a very powerful symbolic benefit.

When I first came to D.C., there was only one other member of Congress who regularly rode a bike—a guy named Dave Minge from Minnesota. I’d mostly encounter a few random bike messengers. That has changed dramatically. Part of it is the expansion of the city bike program. But part of it is that we’ve promoted it here on Capitol Hill. Every day, you see staffers walking past with their helmets and their backpacks. People recognize that it’s a healthy, fast, economic way to transport—and it’s fun. And when you pull up to somebody at a stop light on a bike, there’s no road rage, there’s no snarling.

Portland is world-renowned for its bike culture. I love the bike “greenways” like Salmon and Ankeny—lower-traffic streets where bikes and cars share the roadway. What can other cities emulate about Portland when it comes to cycling safety and infrastructure?

Bike boulevards are something that are taking hold, in part because they work. They promote safer bicycle transportation but, also, when you put facilities like that in—it encourages others to ride a bike.

The bike and traffic-calming strategy on Harrison & Lincoln [in southeast Portland] has not only made it safe to cycle but it has made a difference in terms of the quality of life in the neighborhood. Since we put in that facility [a designated space engineered for bikes], property values went up. Not only is it more attractive, pleasant, and safe—people recognize it and it’s a more valuable place to invest.

What can Portland and other cities do better, as bike and pedestrian accidents are rising?

Part of what we’re seeing is the hangover effects of COVID. People are less attentive, less patient. It’s disturbing. We are watching an epidemic of bike and pedestrian injuries and fatalities. We’re losing ground when we shouldn’t. We’re investing huge sums of money now through the infrastructure legislation we passed [the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act]. There are 473 communities that have a federally-funded planning process for bike and pedestrian activity. We’re putting an extra $1 billion per year into facilities. And it’s really encouraging.

Let’s talk about your bill, the Domestic Bicycle Production Act, which would incentivize U.S. manufacturers to produce bicycles here—specifically e-bikes. Why is domestic manufacturing so important? What is your ultimate vision for this bill?

Early manufacturing efforts for bicycles really were the cornerstone for the manufacturing [transformation] in the United States. In fact, the bicycle was also the foundation for the aeronautics industry. It was a couple of bicycle mechanics—the Wright Brothers—who developed the airplane. Over 110 years ago, there was a bicycle messenger service in Seattle that grew into UPS. There are a whole host of jobs related to the manufacturing function of bicycles, and we’ve lost that. We have a tiny percentage of bicycles made in the United States these days: less than 2%.

It doesn’t have to be that way. We want to make sure that we make it easier to manufacture bicycles here. First, we suggest in this legislation: Place a 10-year tariff suspension on the importation of components needed to build a bike. This is an important cost benefit. We want to encourage companies to manufacture electric bikes by building a transferable e-bike production tax credit. And finally, we want to help expand our existing manufacturing base by providing loans to purchase equipment and increase capacity for domestic bicycle manufacturing facilities.

We think if we can take these steps, we can help build the momentum again for manufacturing bikes in the United States. And in Portland, as you know, there are a number of firms that make handmade bikes. They tend to be pricey—well, not as expensive as your first car or your first house. They’re really fabulous. We want to build on that momentum.

But also make bicycles that are more affordable for everyone, I’m assuming.

Yep!

The Biden Administration is planning big tariffs on Chinese goods, including e-bike batteries and other components. Your bill wants to exempt these items from such tariffs. Why are tariff exemptions a crucial part of this plan to build up domestic infrastructure?

We have a significant tariff burden, in terms of what we’re trying to do to push back some on the Chinese. I don’t want to fight that battle. I just want to make sure we’re not putting the burden on U.S. manufacturers as we’re trying to get this off the ground. This is something strategically that’s been done in the United States for 120 years—back to when Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft were presidents. Giving domestic manufacturing a bit of a break with tariff rates.

Do you really think it needs a 10-year suspension? Couldn’t it be done in five years?

We’re not talking about a temporary, short-term initiative. We’re talking about readjusting the mindset to domestic bicycle manufacturing. We want to build up the infrastructure, we want to create a market, have people thinking about a bike that’s made in America. We ought to be able to provide that benefit, so these companies can get established and grow. I think in the course of 10 years, they’ll be able to function on their own. We’ve got a real problem competing with bikes from China. They are massively subsidized by the Chinese government. And this is a way to help offset that.

Does the Domestic Bicycle Production Act have a chance of passing this divided Congress?

I don’t know. We’re building support; we’re urging people to help us. There are people who are eager to be doing domestic manufacturing. We’re adding their voices. It’s not something that gets massive pushback from big organizations and special interests. So if things go right, it might be possible to tuck it into legislation that’s going to pass toward the end of the year. This is the most efficient form of transportation in the world, and we want to make sure the United States is part of this growing movement.

You launched the Congressional Bike Caucus in 1996. What does it do? Who else is on it?

I founded it to make the federal government a better partner for livable communities: places where people are safe, healthy, and economically secure. This agenda does not have to be partisan. I talk a lot about “bike-partisanship” because I believe bikes are something that can bring us together rather than divide us. My friends Vern Buchanan (R-Florida) and Ayanna Pressley (D-Massachusetts) co-chair the Caucus with me. It’s made up of more than 80 members across the political spectrum.

How have the Caucus’s goals changed over the last 30 years? It seems like general bicycle awareness has gone up but also cars have gotten bigger and safety hasn’t improved. Most cities are totally blowing their Vision Zero goals.

When I first came to Congress in 1996, bike infrastructure only received a sliver of all federal transportation spending. Today, we’ve created a national movement shaping communities large and small. There’s a gusher of funds available to build out pedestrian and bike infrastructure. This is the first administration where we’ve had a president that is so committed to rebuilding America. Now it is about implementation, helping communities take advantage of the funding to build safer, more connected networks.

Despite this progress, the transportation industry has not done its part. Cars are bigger, which makes it harder to see pedestrians. And as I mentioned earlier, we haven’t fully recovered from the recklessness seen during COVID.

We need to take seriously the safety of all road users, not just motorists. Many places are just starting to build out cycling infrastructure, and we should double down on these investments. We can also do more to harness technology like automatic emergency breaking for cyclists and pedestrians that would prevent crashes from happening in the first place.

What are your plans after you retire from Congress?

After 28 years in Congress, I’m looking forward to spending less time on airplanes and more time in Portland, helping the city regain its balance. As a local elected official, I helped Portland become one of the most livable cities in America. I’m convinced we earn back that reputation. There are important projects that can help revitalize our community. I look forward to continuing this work as a civilian.