MIT Researchers are using neural networks and haptic feedback to make conversations easier to navigate.

Wearable electronic devices today are, for the most part, toys for narcissists.

Think about it: Fitbit is great at gathering data about your own body, Snap Spectacles captures the world through your own eyes, and even the Apple Watch offers an inwardly focused information stream. What if, instead, wearables were made to listen and help communicate to the world around you?

That's the goal behind a wave of interesting projects, including one announced this week by a group of scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, and an ongoing project from a Houston startup. Both have created wearables that not only gather sound but communicate with the wearer using tactile or haptic feedback that doesn't require a visual display. This could open a world of new use cases for wearable devices.

A pair of graduate students from from the MIT lab are slated to present a paper at next week's Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence conference in San Francisco highlighting how machine learning can be used to detect emotion in real-time speech and then communicate that to another person.

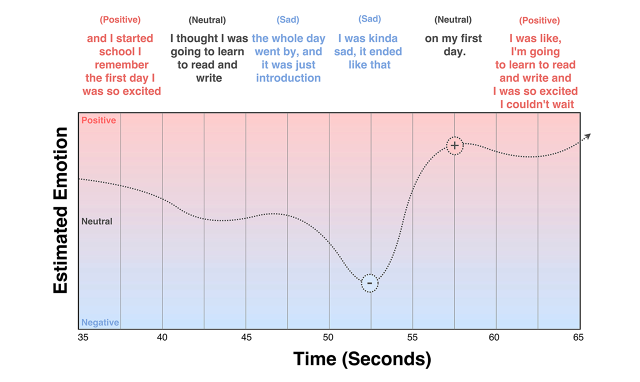

Their system takes spoken-word transcripts, sound samples, and data from a Samsung Simband, including a speaker's electrocardiogram readings and skin temperature measurements, and feeds it into a neural network. The network is trained based on human-labeled speech snippets to use all that information to detect the speakers' emotional states, which the researchers report it does at a rate 18% better than chance and 7.5% better than previous approaches.

Clik here to view.

The resulting emotion, once detected, can then be transmitted to another person. This technique could be applied, for example, to people with Asperger's syndrome or other conditions that can make it difficult to perceive human emotions. Now they could receive real-time feedback on how their conversational partners are feeling, says Mohammad Mahdi Ghassemi, one of the coauthors of the paper.

Clik here to view.

"If you want to navigate from one point in San Francisco to another or one point in Boston to another, you can pull out a piece of technology—Apple Maps, Google Maps or whatever—and it will navigate you from Point A to Point B," he says. "Navigating a Thanksgiving conversation can be just as complicated, and there's no guidance on it."

Future research is likely to streamline the approach. That means potentially limiting the input to just spoken audio rather than biometric readings, which could make the tool more practical for real-world scenarios where conversation partners won't freely give you a feed of their biometric data. And it would likely use real-time notifications, which could discreetly notify users through a wearable device about when a conversation starts going sideways.

"If we're assessing in an interaction that a conversation is getting, let's say, awkward, or negative, the wristwatches they're wearing will buzz twice," says Ghassemi. "It can sort of cue you in that you might want to change gears."

Smartwatches are already being hacked by people with difficulty hearing and seeing to serve as an alternative input channel. Accessibility consultant Molly Watt, who has severely impaired vision and hearing, wrote a blog post in 2015 about her success with the Apple Watch. The device allows her to exchange simple messages from friends and family with just a few taps, even in environments where she can't otherwise easily see or hear, she wrote.

"Mum has certainly found benefit in the 'tap' for getting my attention when I am in my bedroom without my hearing aids on," she wrote. "I feel the nudge to get a move on or she wants my attention for something."

A more specialized device called The VEST, developed by Houston startup NeoSensory, goes further: It translates sounds into vibrations from 32 motors distributed across a user's torso. NeoSensory cofounders David Eagleman and Scott Novich, both neuroscientists, say the VEST can potentially help deaf and hearing-impaired people learn to recognize sounds and even spoken words by training themselves to recognize the different vibrations from the device.

Clik here to view.

Research shows that people can learn to perceive signals normally received through one sense when it's delivered through another, meaning deaf people can learn to feel sounds or blind people can hear images, says Eagleman, the company's chief science officer and the host of PBS series The Brain with David Eagleman. In a TED talk filmed in 2015, Eagleman screened footage of a profoundly deaf man successfully using the VEST to recognize spoken words, explaining the devices could be up to 40 times cheaper than the cochlear implants now typically used to enable deaf patients to hear.

"We have people wear the vest all day long, and they play this whole suite of games that we have on the phone," Eagleman tells Fast Company. One game triggers a vibration corresponding to a particular spoken word, then asks the user to choose between two options, he says.

"At first, you're completely guessing, because you've never felt this before," Eagleman says, but users get better with practice. "The younger the subject, the better the learning is—the better and faster the learning is."

Since then, the NeoSensory team has been refining the algorithms that determine how the motor vibration patterns shift in response to different sound. The company's also been streamlining prototypes of the VEST with an eye toward manufacturing the devices later this year, says Novich, the chief technology officer.

"You can wear them underneath your clothing," he says. "Nobody knows you really have them on, they're really silent, last all day on a single charge, and they're totally robust."

And once the VESTs are released to the public, even people with no hearing impairments may be able to benefit, since an API will let developers experiment with sending arbitrary signals to the vibrating motors from a linked smartphone. That could let the devices be used to transmit anything from infrared images to financial data to video game-enhancing feedback.

"We can think of like 25 things that we would be awesome data streams to feed in, but there are going to be 25,000 things to try that we haven't even thought of," says Eagleman.