Artist David Franklin was sitting on a tree stump in rural Washington state when he answered a phone call that would change his life.

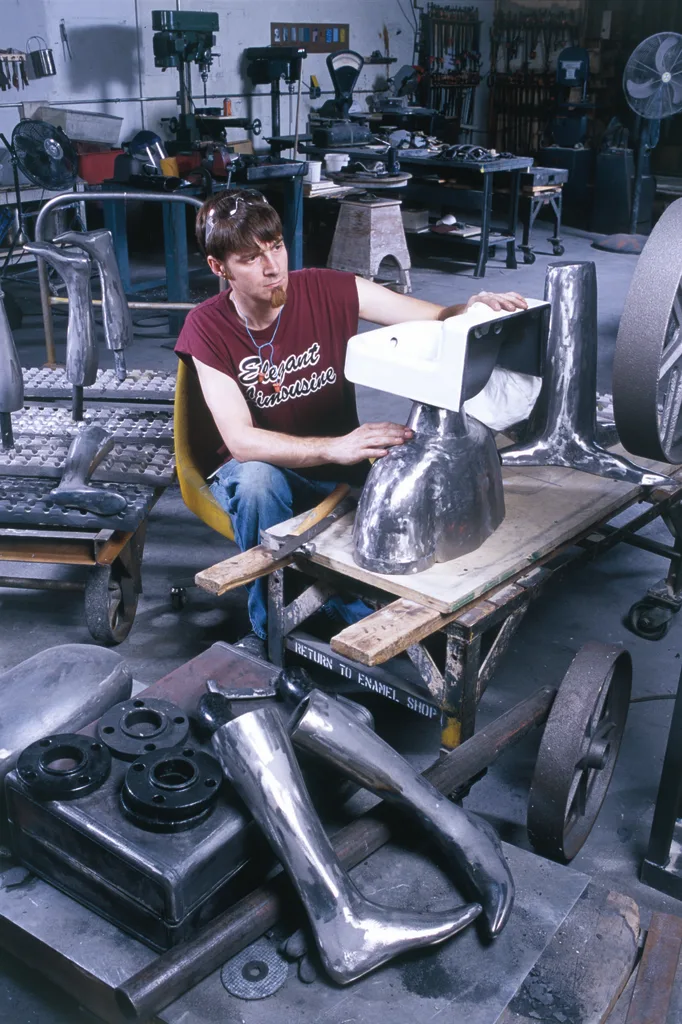

In the early 2010s, Franklin was having difficulty finding creative work, and had taken a position as a timber cruiser, taking measurements in remote groves of trees for a forestry company. He had also applied for a role in a factory. But it wasn’t an ordinary manufacturing job. It was a specialized residency program that places a dozen artists each year in the Kohler Company’s Wisconsin manufacturing facilities, where they create art with the same ceramic or metal foundry equipment factory workers use to make plumbing fixtures.

While out at the forest worksite, Franklin found a spot with cellphone reception and a stump to sit on for a phone interview that helped win him a seat in the program. Like other artists who’ve gone through the residency, he found the experience to be life-changing, exposing him to new tools and practices beyond the woodcarving techniques he was most familiar with. It also opened the door for years of public art commissions, says Franklin, who will soon have a major piece displayed at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium.

“It was just really cool,” he says. “I love working and making things with my hands, and then I was in this atmosphere of this bigger art world that I’d never really experienced before, and that was incredible.”

The residency, known as the Arts/Industry program, is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. It’s a collaboration between the family-controlled Kohler Company and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center museum in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, that today gives artists three months of unique access to industrial equipment, materials, technical assistance, housing, and a small stipend. It also provides inspiration and ideas to Kohler’s artisans and designers, influencing the look of some Kohler plumbing fixtures like the company’s Artist Editions line.

Even as art residencies have become more prevalent, Kohler’s residency is still an unusual opportunity. So much so, that one recent application cycle attracted more than 600 applicants for 12 annual slots—six in the foundry, six in the pottery—making it essentially as selective as an Ivy League university.

“Kohler’s residency is hands down one of the most unique residencies in the world,” says artist Beth Lipman, who’s participated in both the pottery and foundry residency and served as program coordinator for about five years. “There is not [another] consistent, long-term residency that anyone can apply to go work in a factory to create art in this way.”

A factory comes to life

The program got its start after a 1973 contemporary ceramics exhibition at the Arts Center titled “The Plastic Earth.” At the time, says Arts Center Executive Director Amy Horst, the creative world rather sharply delineated between craft work and the fine arts. But Ruth DeYoung Kohler II, who then led the Arts Center, brought artists with work in the show to tour Kohler’s industrial pottery facility, where they were enthralled by the ceramic work being done. She soon invited artists Jack Earl and Tom Ladousa to spend a month doing ceramic work in the factory, then expanded to the formal residency program with help from her brother Herbert V. Kohler Jr., who then headed the Kohler Company.

“He said, ‘Ruthie, I’ve got the factory, you’ve got the artists, let’s see if this will work,’” says Laura Kohler, the company’s chief sustainable living officer and Herbert Kohler’s daughter.

At the time, most artists hadn’t spent much time in factories, and many Kohler factory workers hadn’t had much exposure to the art world. But artists were quickly impressed by the workers’ levels of craftsmanship and deep expertise, and factory employees appreciated artists’ willingness to work long days to master new techniques and get as much done as possible in their limited time on site. “The mutual respect that was formed and the energy that was created between them was really what solidified the program for 50 years,” says Horst.

Franklin, for example, found himself bonding with factory associates over a project turning wood carvings into molds for schools of ceramic fish, a natural conversation starter in a workplace just a few minutes’ drive from Lake Michigan. “The fish thing just resonated with people,” he says. “The fishing culture around the Great Lakes is huge.”

A hard hat residency

The residency doesn’t require that applicants have experience in ceramics or metalworking, and many artists have backgrounds in other disciplines. That can make for a steep but rewarding learning curve as artists don hard hats and safety glasses and learn to use new equipment to produce work on an industrial scale. Residents are expected to leave one piece with the Kohler Company and one with the Arts Center, but the two works can end up being just a small fraction of what they create. “Everyone is seduced by the opportunity to make an incredible amount of objects, so even non-object makers quickly become object makers within that space,” says Horst.

Both the pottery and the foundry have a technician dedicated to assisting the artists, and factory workers often weigh in with tips and troubleshooting advice about, say, making molds, but artists are generally expected to rapidly adjust to the heat, noise, physical labor, and safety protocols inherent in factory work.

“It can be hard physically, but it’s very rewarding,” says conceptual artist Edra Soto, currently doing a second residency in the pottery studio. “Being removed from my daily life in a studio with technical support is like a dream come true for an artist like me.”

Soto, a Puerto Rico-born artist now based in Chicago, has used the space for a variety of projects. One transforms cleaned up cognac bottles found in her neighborhood into works of art. Others include colorful ceramic theater masks and tiles decorated with colors inspired by Puerto Rican architecture. “It’s three months, but it goes really fast, so one thing that I was very mindful about was to just select a few projects that I could focus on and then expand on,” she says.

Other artists have found ways to work with forms already produced by the Kohler factory. Willie Cole, a New Jersey artist who held a pottery residency in 2000 and now has an exhibition at the Arts Center, says at the time he had been working heavily with found objects, so some of his work at the Kohler plant included animal sculptures made from ceramic bits and hardware culled from imperfectly formed fixtures that would have otherwise been discarded. “I like to create spontaneously, so I had all these pieces laid on the table, but it wasn’t what I was working on most of the day,” he says. “It was something I would walk by each day, and then move a little piece around like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Once they’ve experienced what’s available, artists sometimes return for second residencies to expand on their work or try new techniques. During a foundry residency several years after her time working for the museum, Lipman created a series of cast metal works titled Distill, made from cardboard dioramas holding miniature furniture and “ancient flora” like lichen and ferns. She credits her time working for the residency program with giving her the knowledge to take the project as far as she did, like adding chrome, enamel, and a rust patina to the works.

“I witnessed countless foundry residents going through,” she says. “I was able to kind of assimilate the information as if I had had that residency, but it was just from witnessing their process a little bit.”

Art as a corporate imperative

The Kohler institutions have generally blurred the lines between art and industrial design. Artists, including past residents, designed stunning public restrooms for the Arts Center’s main building and its Art Preserve, which archives and showcases spaces like artists’ homes and workspaces. The washrooms—the museum’s preferred term—are themselves works of art that can be almost intimidating to use for their intended purpose, including one designed by Lipman tiled with ceramic replicas of local flora specimens from the University of Wisconsin. And an installation based on the Kohler factory studios, on display at the Arts Center as part of the 50th anniversary celebration, feels like a cousin to the artist spaces showcased at the Preserve.

Work produced at the Kohler residency is routinely exhibited at the company’s showrooms around the world and, for pieces that can withstand the weather, along an outdoor art walk near company headquarters. The company bought one of Franklin’s fish pieces and displayed it at its Kohler Experience Center in West Hollywood, helping win the artist additional commissions from remodeling homeowners impressed with his style, he says.

“Our philosophy with Arts/Industry is to show the work,” says Laura Kohler. “Not store the work, but to get it out and let people experience it.”

Over the years, art rooted in plumbing materials has had its influence on Kohler’s own designs. The Artist Editions line emerged in 1981 after pottery resident artist Jan Axel developed a sink design that caught the eye of the Kohlers. “We liked it so much, we wanted to make it commercially,” says Laura Kohler. “I think my father probably saw it and said, ‘I want to see if I can make that at scale.’”

Artists have over the years continued to put Kohler manufacturing technology to new uses. After artists recently inquired about a 3D printer in use at the factory, the company purchased a second one for their use. Soto recently harnessed it to help produce scaled up versions of her masks. A new “MakerSpace” program brings in artists by special invitation—that’s where Franklin created his new work for the Shedd, along with a new set of fish for Miami’s Kohler Experience Center, and artist Patty Chang will soon be working there on a piece that will be shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some artists have recently worked with material from Kohler’s WasteLAB, where the company has in recent years devised ways to harness scrap that would otherwise go to landfills. And to finish some of his fish, Franklin and some of the factory staff experimented with physical vapor deposition (PVD), a technique that had previously only been used at the factory for applying glossy finishes to metal fixtures like faucets, rather than ceramics.

“It turned into a beautiful gloss—some of them are gold, some of them are rainbow,” says Laura Kohler. “That’s the kind of discovery that happens with this collaboration.”