Deepfakes have already been a problem in the 2024 presidential election—and could potentially become a bigger one as November 5 draws near. But a new Chrome browser extension claims it can help people determine which audio clips they hear are legitimately from the candidates (and others) and which are fake.

The Hiya Deepfake Voice Detector uses artificial intelligence to determine if the voice on screen is legitimate or faked. The company claims the tool has a 99% accuracy rate and says it can verify (or debunk) audio in just a few seconds.

“Our models are trained to detect subtle audio artifacts unique to AI-generated voices—imperceptible to the human ear but identifiable by machine learning algorithms—and just a second of audio is enough to detect their presence,” Patchen Noelke, vice president of marketing for Hiya, tells Fast Company.

I put the free tool to the test and found that while it certainly does catch some deepfakes, its accuracy varied.

Testing the browser extension

Founded in 2015 as part of online directory Whitepages, Hiya is in the business of providing services that screen calls for spam and fraud. Today, the company has more than 450 million active users, according to its website.

After installing the Hiya’s extension from the Chrome Web Store and registering, users open the tool in their browser and click, “Start analyzing,” when they’re watching a video or listening to an audio clip whose origin is in doubt. Users are limited to 20 queries per day.

While it’s certainly helpful to have any sort of tool that identifies even a percentage of the deepfake video and audio clips (others, though not browser extensions, include Pindrop Security, AI or Not, and AI Voice Detector), my own tests with the Hiya Google Chrome app found some notable holes.

Using real and deepfake soundbites that appeared in a Washington Post story, I had the tool examine both a real and a fake clip of Kamala Harris. To its credit, it did call out the deepfake, but the tool said it was uncertain about the authentic clip of Harris.

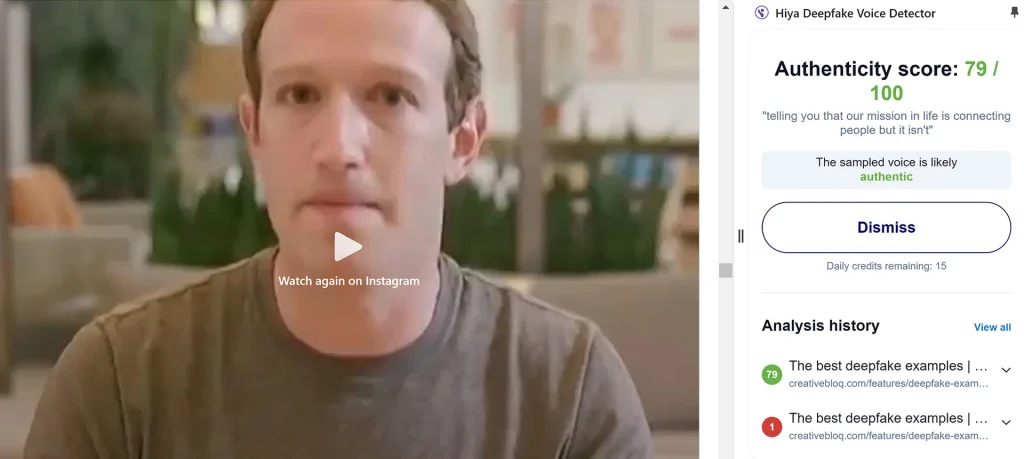

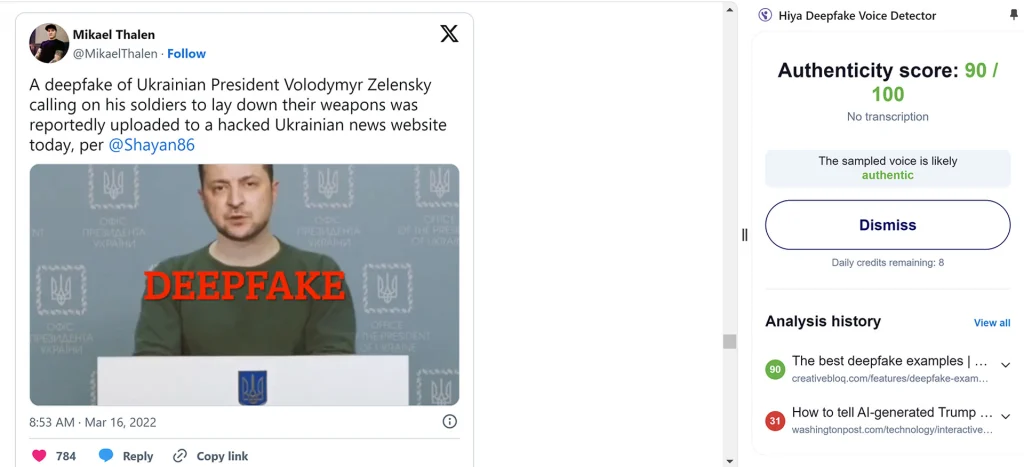

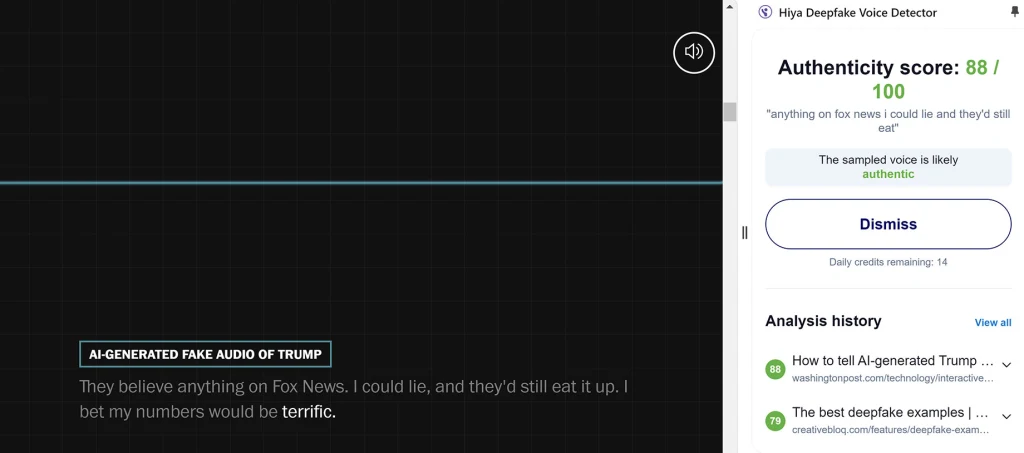

An AI-generated audio file of Trump was judged as likely authentic, with an authenticity score of 88 out of 100. And a confirmed deepfake of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy instructing his troops to lay down their weapons got an even higher authenticity score of 90.

Deepfakes of Mark Zuckerberg and an AI-created video that featured a voice actor imitating Morgan Freeman were also wrongly deemed authentic, with the fake Zuckerberg earning a score of 79 and the fake Freeman getting a 72.

A deepfake of Kim Joo-Ha, a news anchor on Korean television channel MBN (which was presented by the network last year), was spotted immediately as a fake, however, earning a score of just 1.

Noelke acknowledges that the deepfake detector has some limitations. Freeman and Zelenskyy fakes were made with voice actors rather than AI, which is why they weren’t detected, he says. The score on the Trump deepfake changed depending on how much audio was sampled, Noelke notes. (“When scoring the entire file instead of analyzing it in 4-second chunks, the overall score is 63%, placing it in the inconclusive category,” he says.) And the Harris deepfake had loud background music that interfered with scoring, which is why the tool was uncertain.

“The way we designed the Chrome extension is it gives you a confidence score and you do have to judge for yourself,” he says. “There are some things that make it harder [like] the quality of the sound and background music and other things can affect it. It can definitely fail. It’s definitely not 100%—and that’s why we deliver the results the way we [do].”

The app also only analyzes the audio portion of a video, so if a politician, celebrity, or anyone else’s image is digitally inserted into a video where they do not actually appear, it cannot flag that as inauthentic. We tested this on a Back to the Future clip that swaps Tom Holland and Robert Downey Jr. for Michael J. Fox and Christopher Lloyd.

Deepfakes and the election

AI has already thrown a wrench in the 2024 presidential election. In January, a deepfake robocall that reproduced the voice of President Joe Biden urged Democrats not to vote in the New Hampshire primary. Since then, there have been false images that show everything from Taylor Swift endorsing Trump to Kamala Harris in a communist uniform to Donald Trump dancing with an underage girl. And this summer, Elon Musk shared a deepfake that mimicked the voice of Harris claiming to be a “diversity hire” and saying she didn’t know “the first thing about running a country.”

Musk, when criticized, later said the video was intended as satire.

Several states have enacted laws regulating election deepfakes, including California, Texas, and Florida. But only three of the eight swing states that are expected to help decide the 2024 presidential election have laws on the books—Michigan, Wisconsin, and Arizona. (Legislation is pending in North Carolina and Pennsylvania but is unlikely to pass before the election.)

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) quickly made AI-generated voices in robocalls illegal, but federal officials have been slower to act on other mediums. And when it comes to online content, which is where these most frequently spread, that continues to be the wild west. The FCC says it does not regulate online content.

Update, October 17, 2024: This story has been updated with a response from Noelke about the specific audio clips tested.