October has long been associated with ghosts—from ancient Celtic festivals to ward off restless spirits after harvest time to the modern standby of using an old sheet to make a last-minute Halloween costume. In the middle of the 19th century, however, popular portrayals of ghosts became a year-round staple, in part because photographers discovered that they could depict them.

The first ghost photographs were accidents. Early cameras required 30 seconds or more to take a photo. If someone wandered briefly into the shot, the resulting picture would contain their ghostly trace superimposed over substantial furniture, buildings or people who had held still for the full exposure.

When shrewd photographers realized that the inconvenience of long exposure time could become an asset, detailed directions for creating these illusions proliferated. Photographers could cut ghost figures from transparent material and place them onto glass negatives or inside camera bodies. Or they could make real people half-transparent through tricks of double exposure.

As early as 1856, experts gleefully noted that one could create images of ghosts “for the purpose of amusement.” Commercial photographers began producing this spectacular phenomenon for fun and profit and—as I have found while researching early portrait photography—thereby helped feed media fascination with all things ghostly.

Turning accident into amusement

Photographs became collectible amusements partly thanks to the midcentury invention of the stereoscope—a device that created three-dimensional optical illusions.

Stereoscope cards contain two pictures of the same scene, photographed from slightly different angles. A viewer selects a card, inserts it, and then presses the instrument to their face. The device isolates their eyes, so each sees only one picture. As the brain, trying to avoid double vision, merges these images into one, the result is a 3D effect.

In the 1850s, reading aloud was the primary form of at-home entertainment. Daily newspapers ran no images, and the technology to reproduce photographs in books or periodicals was still 40 years away. But this affordable gizmo could bring the whole world into your living room.

My archival research has turned up newspapers full of articles and ads promoting stereoscopic “marvels.” The London Stereoscopic Co. advertised “effects almost miraculous” and marketed the device for family entertainment. By 1856, a mere two years after the company’s founding, its catalog listed over 100,000 cards, including views of dramatic landscapes, exotic tourist destinations, famous portraits, and card sets that told stories.

Among these collections of sights unseen were plenty of ghostly images. The Ghost in the Stereoscope, a colorized card, shows two men in open-mouthed surprise at the sudden appearance of a ghost at their supper table. The title signals the jump scare that the image maker hoped would likewise amaze the viewer when the 3D ghost loomed before their very eyes.

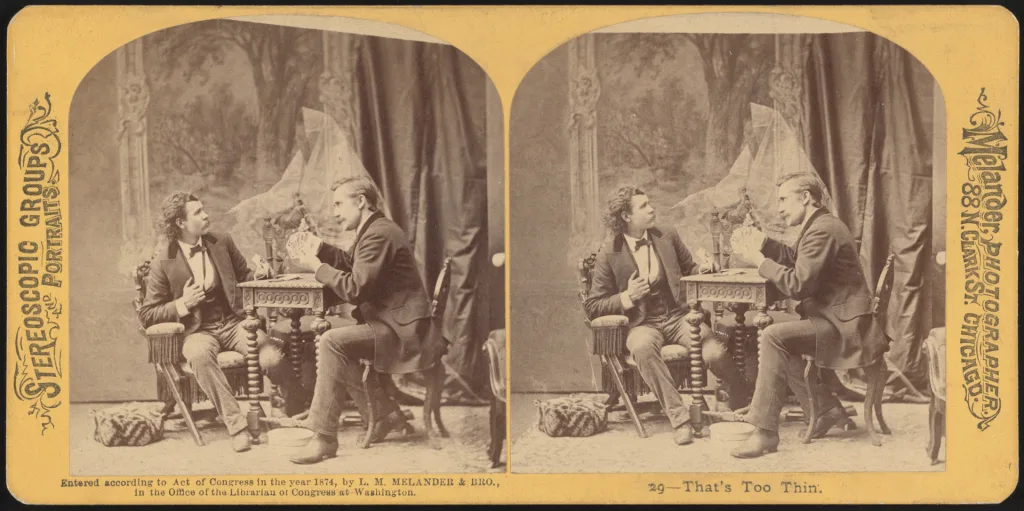

On another card, That’s Too Thin, a ghost points an accusatory arm at one man sitting at a gaming table. The 1876 guide How to Write Letters lists “too thin” among its “slang words and phrases” to be avoided for their “low associations and vulgar ideas,” which suggests that the offender is doing something unseemly for a respectable man. This visual joke relied on a pot-kettle formula: A figure so thin as to be see-through is calling out someone else as “too thin.”

Popular ghosts

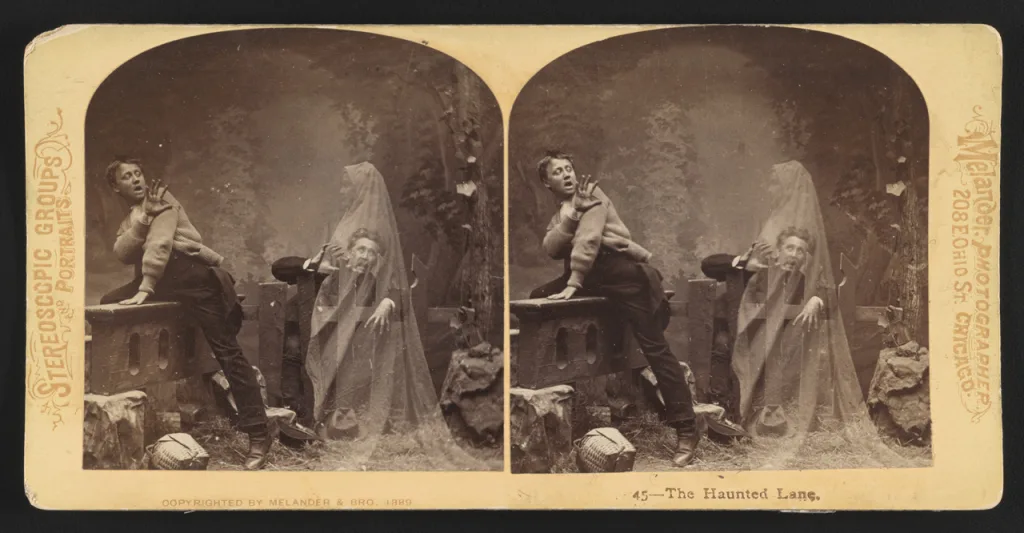

Nothing was meant to imply that these were pictures of actual spirits. Some—like The Haunted Lane, in which two men who cower in supposed terror from a ghost are obviously photographed in a studio with “lane” props—were so melodramatic as to be funny. Others were more melancholy and featured mourning husbands whose ghost-wives played the piano beside them, or orphaned children whose ghost-mothers watched over them from beyond the grave. All of them were performances.

And all of them helped stoke a midcentury market hungry for ghostly thrills. In 1859, novelist Wilkie Collins published his spectral The Woman in White in installments in Charles Dickens’s weekly magazine. It sold more than 100,000 copies and launched a decade-long craze for hair-raising sensation fiction.

The Illustrated Police News, launched in 1864, contained supposedly true tabloid-style stories that often featured ghosts. And in 1862, John Henry Pepper, a British scientist and popular lecturer, refined a projection technique that could create apparitions onstage during live theater productions. Commonly known as Pepper’s Ghost, the dramatic illusions began appearing immediately on both sides of the Atlantic.

Some stereoscope cards referenced multiple forms of popular entertainment to create ghost images that worked as layered visual jokes. The 1865 card A Dream After Seeing Pepper’s Ghost is a great example of how the Victorian penchant for allusions and wordplay found its way into this visual pastime.

The sleeping young woman’s “dream” is a photographic ghost: The looming, gauzy figure filling the dark space of the window beside her bed would have appeared to float in 3D stereoscope. “Seeing Pepper’s Ghost” obviously refers to a play she has attended: Her fine clothes tossed haphazardly on the furniture indicate a late evening out.

But the ghost has the head of a cow and wears a necklace on which is lettered “MUSTARD.” A Victorian viewer accustomed to wordplay riddles would realize that this ghost-of-pepper also implies that the sleeper ate too much of an overly seasoned roast beef dinner, for indigestion was commonly understood to cause bad dreams.

Together, these details may allude to Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. A theater company in 1865 would undoubtedly use the sensational new Pepper’s technique to place the ghost of Jacob Marley onstage to torment his former business partner, the miser Scrooge. And Scrooge quite famously dismisses Marley’s ghost initially as “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard”—that is, as merely a bad dream brought on by overeating. A clever viewer would delight in puzzling through these playful layers of stereoscopic magic.

There were, of course, also Victorian photographers who purported to capture actual ghosts. They sometimes worked with mediums at séances, and their claims to record the spirit world engendered huge controversy.

But in the Halloween season, it’s fun to contemplate the lighter side of this history, when an appetite for haunting tales inspired photographic ghost effects that seem delightfully ahead of their time.

Andrea Kaston Tange is a professor of English at Macalester College.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.