The screech of dialup modems. Brightly colored, blinking text scrolling across a flickering screen. Web rings and under-construction GIFs and tinny Pearl Jam MIDIs.

For years, the 1990s Web has mostly been a set of punchlines for those who were online early enough to remember it, the virtual equivalent of JNCO jeans, Pogs and the Macarena.

But lately, a growing number of developers have sought to bring back its early aesthetic and, more importantly, the spirit of innovation and community they say prevailed on the Internet of the day. And that movement has spread to include programmers and designers who are too young to remember the '90s but still admire the spirit of the early, less commercial web.

Earlier this month, author and developer Paul Ford launched the experimental and deliberately retro hosting provider Tilde.club on a whim, after having a few drinks and reminiscing about what he called"the early personal web."

According to Ford's widely circulated Medium post announcing the service, thousands of users applied for an account. And those users quickly logged in, swapping ASCII art images and building websites from hand-coded HTML, according to Ford's post.

"A lot of the pages were purposefully retro and '90s-looking; others were meditations on the meaning of tilde.club," he wrote in the post.

Tilde.club, which takes its name from the Unix tradition of preceding a user's home directory with a ~ mark, has received donations of money and technical help, according to Ford, and a screenshot he posted of an Amazon Web Services statement suggests the hosting expenses are relatively minimal as, he implies, are any expected financial returns.

"There is no hurry to join," Ford wrote. "There is no business model, no relevance for brands and nothing to optimize. The site does not compete with anything--for it is just a single computer like millions of others."

Though Ford playfully presents himself as a crusty old system administrator of the type mocked in old Dilbert cartoons--"Like any system administrator, I will be slow to respond, will get everything wrong, and will act imperiously while never acknowledging wrongdoing," he wrote in an email to new users--he promises a level of inclusiveness that's been far from universally present in the tech world, either now or in decades past.

"This thing is a de-facto whitey sausagefest so everyone be actively, aggressively cool and sweet and remember that the only binary that's real is the one that we use on our microchips," he continued in the email.

But it goes beyond Tilde.club. Designers and developers across all corners of the internet are embracing this aesthetic.

"Certainly there is a desire for those more earnest days of the Internet," says Ben Brown, cofounder and CEO of the software design and development house XOXCO. "Those days of the quiet, nerdy, artistic web are very appealing."

Brown's firm created Make Pixel Art, a deliberately lo-fi app with an interface reminiscent of early versions of Microsoft Paint. For Brown, the medium hearkens back to a time when those Internet communities felt like their own places, separate from the physical world. Back then digital media had a distinctive pixellated look simply because of the limitations of computers and displays.

"It was clearly an Internet thing or a computer thing, not some sort of hybrid media experience," Brown continues. "Everything is now so high-res and so glossy that the sort of raw digital natures of things are lost."

And quick glance of platforms like Tumblr reveal that pixel-heavy style still appeals to a wide swath of Internet users, including digital natives too young to remember the early days of CompuServe and AOL.

"There's a cross-generation community of pixel art," he says, from teens to nostalgic early adopters now in their forties and beyond. He believes the early sense of community has been somewhat lost as technology's improved and become more a part of everyday life.

"Being able to be online on a Unix box or on The Well or one of those early community tools really did give you a sense of being in a physical place with people," he says. "A lot of us got online in the early days to create a community of people that we couldn't create in our physical lives for whatever reason."

Kyle Drake, the creator of the web host Neocities, says he was motivated less by nostalgic for the look-and-feel of '90s free hosting provider GeoCities than by the desire to create a new platform with the same spirit of experimentation.

Filling out a Facebook profile or even populating a site on a blogging platform doesn't promote the same level of experimentation as crafting a personal page in old-school HTML, he says.

"I don't miss the tables; I don't miss the crappy layout; I don't miss the embedded MIDI files," says Drake. "I miss web surfing. I miss the creativity, the spontaneity and uniqueness."

Drake misses the old, weird Internet, where it was easier to surf from a pre-IMDb movie fan site to a crafter's page of photos to something even more esoteric.

"What I'm trying to do with Neocities is re-enable that creativity, and show people that it isn't just a nostalgia thing any more," he says, adding that the site now hosts about 26,000 sites and has proven financially self-sustaining. "This is something you can really do."

And while it's certainly possible to build unique and creative sites through services like Tumblr, there's something refreshing about working with raw HTML and not having to worry about the staying power of more elaborate platforms' databases and templating systems, he says.

Even developers who've since moved on from the pre-CSS Internet to building sophisticated, database-backed web apps say there's something pleasantly refreshing about coding sites simple enough to put together with a basic text editor.

"I thought it would be fun to just wing it, and start editing right there on the server," says Mike English, a system administrator and developer with an old-school homepage on Tilde.club, though he's since started storing past versions in Git.

English said his site isn't quite representative of any actual historical Internet era--friends have teased him about anachronisms in his HTML--but is largely modeled off of a type of academic and professional homepages he's always appreciated, which pay more attention to substance than beauty.

"I had always wanted to have a page like academic profile pages--these old pages where the style is just not there, but the content is great," he says. "I thought, okay, this is my chance, I can finally make one of those pages."

Many of the architects of the retro web lament a time when the medium wasn't as dominated by advertising and branding and commerce. Drake emphasizes that Neocities is purely community-supported and plans to revise the site's terms of service to guarantee he won't sell user data to advertisers, and Ford's Medium post reads like the opposite of a typical product launch.

Drake, too, says his site's hosting expenses are likely orders of magnitude less than hosting providers faced in its namesake's heyday.

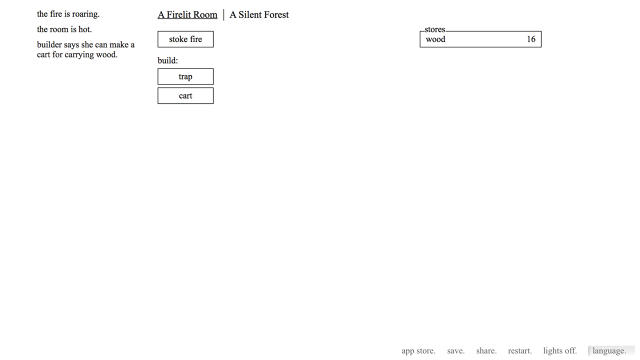

The hardest resource to come by nowadays is often not computing power but manpower, says Michael Townsend, whose Doublespeak Games is known for its critically acclaimed "minimalist text adventure" game A Dark Room.

"You've got limited time, limited skill, limited money--it's much easier to go with the old-school aesthetic."

But old-school graphics don't mean old-school gameplay, he argues, recalling that 20 years ago, even being able to save progress in a console game was a relatively new concept.

"You approach the stuff that you loved from back then but through a lens that is shaped by all the experiences that have come between then and now," he says. "You can revisit those kinds of aesthetics with a lot more tools and a lot more ideas."

Townsend says the success of Minecraft among younger players shows simple graphics don't automatically repel users raised on high-definition video, which is good news for independent developers and studios who can't afford to build games with cinematic video.

Aided by the rise of smartphones and Internet distribution, game developers have also embraced a lo-fi, retro approach, allowing smaller, bootstrapped developers to focus more on imaginative storytelling and innovative game design.

Nostalgic players have recently helped bring about a sequel to the 1980s post-apocalyptic game Wasteland that competes on story, if not on graphics, with the Wasteland-inspired Fallout series and funded a new game in the Shadowrun role-playing universe, with similar mechanics and graphics to '90s Shadowrun games for Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis.

And other indie developers have created games that wouldn't seem out of place on game systems of years gone by, from Final Fantasy-style role-playing games to addictive puzzles.

"The retro aesthetic is really great," Townsend says. "Anything that lowers the barrier to entry and gets more people making things on the Internet is good in my books."