New gadgets are arriving that are designed to show you in real time just what you're breathing in, with Internet-enabled indoor and outdoor air-quality sensors.

But one of these devices' biggest challenges, their makers say, is keeping customers engaged by making sure they understand what the readings mean and how to act on them.

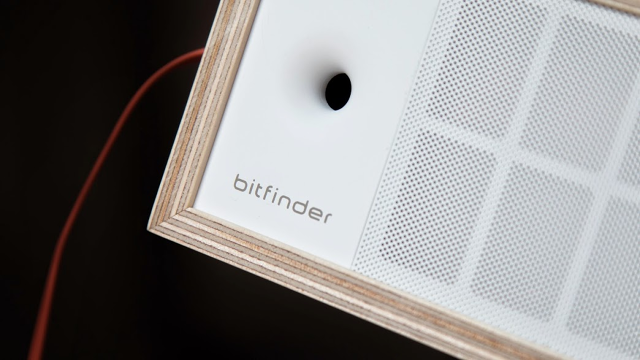

"What we think is really important with this kind of product and services, is that we really need to connect on the human level," says Ronald Ro, cofounder of Bitfinder.

Having participated in the most recent round of the Internet of Things-focused R/GA Accelerator, Ro's company plans to release its Awair indoor air-quality monitor this summer. The speaker-sized units will share the market with existing smart indoor-outdoor weather stations from French firm Netatmo, and ultimately with wearable environmental trackers from Vancouver-based TZOA, also slated for release later this year.

The Awair will monitor air temperature and humidity, along with levels of dust particles, carbon dioxide, and a class of chemicals called volatile organic compounds, which includes solvents like acetone and benzene and a range of various other substances of varying toxicity.

Clik here to view.

Ro says the device will help businesses know when to ventilate a conference room stuffed with carbon dioxide and hot air from a morning's worth of meetings, or make sure they're adequately dealing with chemicals released into the air from overnight renovations. For home users, it'll warn them if their bedrooms are getting uncomfortably dry overnight, or suggest they turn on their stovetop fans if their kitchens fill up with cooking exhaust.

Since most users won't have the same intuitive understanding of CO2 levels and dust particle concentrations that they do of degrees Fahrenheit, the sensors' accompanying smartphone app will offer five color-coded alert levels and text notifications emphasizing descriptions and suggestions, not numbers, Ro says.

"Our first notification will be something like, 'Hey, your environment is better suited for cactus than for humans,'" says Ro, coupled with recommendations for how to improve the situation. Users will be able to give feedback on whether the recommendations were actually practical so the app can improve its suggestions over time, he says.

For its part, Netatmo, which has sold smart weather stations tracking air pressure, humidity, temperature, and air quality since 2012, says its customers remain regularly engaged with the product. On average, users check the corresponding smartphone app about twice a day, the company says.

"Of course, we can't monitor if people act accordingly when they receive an alert (e.g., open the windows when the CO2 level is over 1000)," wrote Raphaëlle Raymond, Netatmo's vice president of marketing, in an email. "However, we have received a lot of testimonials from our customers who are happy to know when to open their windows and have a cleaner environment, especially for their kids."

Since the initial weather stations launched, Netatmo's added an optional rain gauge and recently announced plans for a wind-monitoring add-on. The weather stations also feed outdoor meteorological readings into a live weather map and, as of late last year, are shared with the Weather Channel-affiliated service Weather Underground.

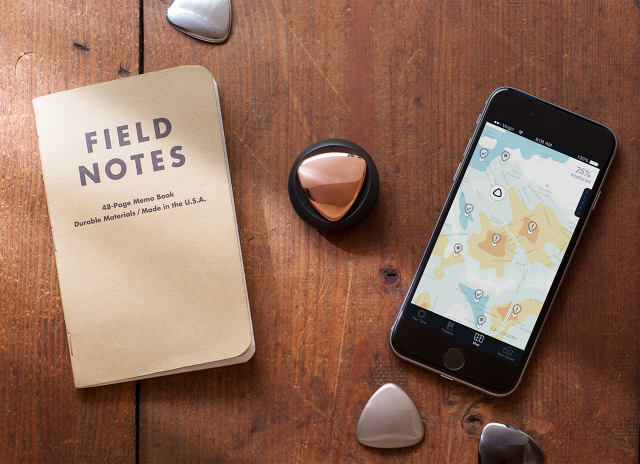

Clik here to view.

And when TZOA releases its lens-cap-shaped trackers later this year, the company plans to build a similar real-time map of outdoor air quality, letting cyclists and pedestrians clip the devices onto their clothes or bags to monitor what's in the air they're riding or strolling through. The company says its sensors will track temperature, humidity, ultraviolet light exposure, and levels of both larger particles, like dust and pollen, and smaller particles, like some found in car exhaust and smoke, that can cause longer-term health problems.

"That data gets pushed out to your smartphone [via Bluetooth], and you can see the number rising and falling, minute-by-minute in real time," says TZOA founder Kevin Hart.

Other users will be able to track those accumulated readings to plan their own trips and see how their neighborhoods stack up to others, Hart says. The app will offer color-coded warnings and tips and an air-quality index number, similar to metrics used by the EPA—the company's been speaking to researchers and regulators about using the data the devices will collect for scientific purposes, Hart says.

And for users who don't always want to wear the sensor, the TZOA devices will also be able to monitor indoor air quality, including when it's sitting at home, docked in its charging station.

"It's very flexible—I know with the Fitbit a lot of people are turned off by the fact that they always have to wear it, so it eventually sits in the drawer," says Hart. "In the future, we're looking at integrating with connected objects, so for example this might tell if the air quality's bad in your house and it needs to turn on an air-quality purifier."