Twenty years ago, in the San Francisco neighborhood then called Multimedia Gulch, a state-of-the-art server from Sun Microsystems began to run a program that would one day lead to more than a million newborn babies.

The machine belonged to a startup called Electric Classifieds, which had plans for a series of sites on the rapidly growing web that would mirror the sections of a newspaper's classified listings. The first section to launch would be the personals, on a site called Match.com.

"Match.com would be the test case to show potential partners and others that the underlying technology worked," says Fran Maier, the site's marketing director at launch and later its general manager, who later went on to lead the Internet privacy group TRUSTe for more than a decade.

Today, Match is the largest operator in what market research firm IBISWorld estimates is a $2 billion dating industry. Roughly 1 in 10 Americans have used at least one online dating service, and most Americans have a generally positive view of online dating as a way to meet new people, according to a 2013 study from the Pew Research Center. After changing hands a few times in the late 1990s, Match is now the centerpiece of Internet firm IAC's digital dating empire, which also includes sites like OKCupid, Tinder, BlackPeopleMeet, and Chemistry.com.

And just last week came the news that Match is going public. According to its SEC filing, the company collected $49.3 million in profit over the first half of 2015. It counts a collective 511 million worldwide users, when customers of all its products are tallied.

The company estimates that Match alone has helped put together more than 10 million couples, who have then gone on to have those million babies, and the company is optimistic it will see a steady stream of new users for years to come.

"Every single person is born single," current CEO Sam Yagan likes to say.

Dialing Up And Hooking Up

When the site first took to the web in April 1995, letting users post profiles and search for potential mates, online dating was still a niche pursuit. Dial-in dating bulletin board systems existed at least as far back as the 1980s, and couples met through early online services like CompuServe—conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh even met his third wife through that network—but for many early Match users, the site was their first foray into online flirtation.

"To be honest, in the early days there was a sense of magic about it, for me at least, and I suspect for other people too, because it was so new and untested," recalls Andrew Gerngross, who joined the site a few months after its launch.

Gerngross, who's now a professional screenwriter, was then working as a software developer in New York. He met a number of women through the site, including his first wife, and still remembers the sheer novelty of browsing the site and connecting with strangers through the web.

"It was the first time I'd actually emailed with someone where I didn't have some professional association or technical interest in sharing something," he says. "This was the first personal thing I'd done on the Internet, and there was some excitement about that."

But that novelty also had many early web surfers apprehensive about posting their profiles online for strangers to see, says Electric Classifieds founder Gary Kremen.

"People were super worried, especially women, about safety and security and anonymity," he says. "The idea of putting out their wants and desires at the time was really alien to all genders."

Kremen and Maier realized early on that the site's success would depend on appealing to women who, according to a Georgia Tech online survey cited in early company literature, made up as little as 10% of the web's 1995 user base.

"We thought that if we got the women, men would follow—women are the scarce resource on the Internet," she says. "For the most part, we were heterosexually focused, although we did have men seeking men and women seeking women."

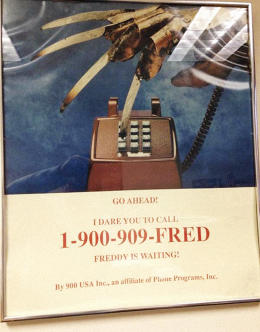

At a time when computer magazines were advertising dial-up singles chat services with names like Sexy Modem and Fantasia Services Unlimited, Match promoted itself as safe, anonymous, and friendly.

"Match.com has always tried to keep it clean," says Anne Wayman, who worked for Match as an editor and copywriter. "[Kremen] understood that—it had to be as clean as you could keep it, given the technology."

Match gave its members anonymous email addresses that forwarded to their real accounts—a big deal before throwaway webmail accounts were widespread—and emphasized that potential matches wouldn't be alerted when you browsed their profiles.

"I had a couple of bad experiences when I went through the personal ads in the newspaper, so for me, that was a real benefit to doing online dating, because I thought it would be safer," recalls Simone Cox, a Bay Area technical writer who joined the service as a beta tester in its first year. "For me, being anonymous was very, very important, and that was one of the reasons why I decided to do the online dating thing in the first place."

Maier made the site's design as welcoming to women as possible. She vetoed a proposed revenue model where users paid per message.

"For women, and women understand this, it seems like you're putting a price on them, it seems like you're trying to buy them," she says. The site also rejected a profile question Maier thought few women would want to answer.

"I said, 'No, we're not going to ask people's weight, forget it—we're trying to attract women, that's such a turnoff,'" she recalls. Instead, "we're going to have body type."

From the site's early days, Maier—who now advises and mentors women new in business and technology—also appeared frequently in the media discussing Match's safety features and decrying the harassment women faced elsewhere online.

"On some services, simply identifying yourself as a woman is the virtual equivalent of walking into a cowboy bar wearing a Wonderbra, boots, and not much else," she wrote in an opinion piece published in the Washington Post in 1995.

The company quickly worked to court the press, capitalizing on the public's quick fascination with online dating and looking to dispel the notion that the service was limited to lonely nerds and weirdos. ("Turn on your computer, dial in to the Internet, and you're ready to hook up with desperate singles all over the world," wrote a business writer for Florida's Bradenton Herald in one early story about the site.)

Maier and public relations director Trish McDermott appeared on national talk shows and newscasts, as did some of the service's successful early couples and more telegenic users. And when the site introduced a membership fee a few months in, McDermott says she still gave free accounts to journalists covering the site.

"It was very, very common for these reporters to meet someone on Match and fall in love, or at least have a serious romance going on," McDermott wrote Fast Company in an email, though she says she doesn't recall any names. "This is one of the ways we built such a strong and positive relationship with journalists."

Scaling Intimacy

Match also ran its own newsletter in which it shared online dating insights from staff and members, including everything from crafting the perfect profile to exploring cybersex. "I had my 1st CYBERSEX experience in the late 70s when the INTERNET was called ARPANET, and I did it on a TTY terminal," began an anonymous letter in one such discussion.

McDermott, who wrote the newsletter's advice column, recalls getting plenty of ordinary etiquette questions from early members: They wanted to know when it's okay not to answer a message, and how long to go before meeting face-to-face or talking on the phone, and whether it's acceptable to send an email instead of making a phone call after meeting in person.

"Really, the early users of Match were the people who were sort of inventing those protocols: what worked and didn't work," she says.

And the newsletter gave them a place to discuss and compare their experiences, even if many of their real-life friends weren't yet dating online. Match wasn't just promoting itself in those early days—it was promoting the legitimacy of the entire nascent industry.

"We had to evangelize for online dating—not just evangelize for Match.com," says Maier. "We were building a market for this."

At the same time, Match's developers were working to stay ahead of a rapidly evolving web. Competing browsers still behaved quite differently, so Match's servers had to detect what software users were running, and send code tailored to work on their machines, says Kremen. And the differences weren't minor: Some browsers didn't support cookies to track who was logged in, and some couldn't even handle images, he says.

When the site launched, it wasn't even clear the web would win out over then-competing systems like Gopher, or that it wouldn't be eclipsed by some technology yet to be invented.

"I had an intuition that the web was going to be one solution," he says. "It turned out to be the only solution."

And most early users didn't have any digital pictures of themselves—Wayman recalls she hadn't even seen a digitized photo until she started working at Match, since she used a text-only network on her home DOS machine—so they'd snail mail or fax snapshots to Match, or need help finding a place to scan them in.

"People didn't have scanners—they had to go to Kinko's," Kremen says. "We built this thing with a database of Kinko's and scanners, so people could get their pictures in."

Plenty of early users only had Internet access at work, which meant Match's servers would see a traffic spike every day after lunchtime, he says.

"I did not have Internet at home, because that was unheard of, at least by me," says Cox, who started a job at Netscape shortly after joining Match. "I was lucky enough, because I worked in high tech—that's another reason that I was able to get involved with it, because at least I had Internet access at work."

Cox is still single, though she says she had a good time on the site—aside from a few matches who weren't quite as advertised when they met up in person—and met a few men she's still friendly with. At the time she joined, most of the men she encountered on the site were also working in technology, she says.

"I figured out that the men that I would meet would have to at least know what a computer was or have a connection to the Internet, so that would weed out a lot of undesirables," she says.

The web soon grew rapidly, of course, and, as the public grew more comfortable with what it had to offer, so did Match. By the end of 1996, more than 100,000 users had registered for the site, which would be acquired the following year by e-commerce firm CUC International. CUC would soon merge with Hospitality Franchise Systems, the parent of hotel chains Days Inn and Ramada, to form Cendant Corp. And after an accounting scandal, Cendant sold Match for about $50 million to Ticketmaster Online-City Search, a predecessor of IAC.

By then, the site had signed up more than 1.8 million total users. Much of the early stigma attached to online dating had dissolved, particularly after the 1998 romantic comedy You've Got Mail, in which Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan get digitally acquainted, says McDermott.

"I think that changed the discourse about online dating to something positive, and that sort of scary belief that you were going to meet a creepy stalker-type person started to dissolve when you saw that the Meg Ryans of the world might be the people you'd be meeting," she says.

By 2000, Match was respectable enough to join Princess Cruises in a multiday millennial Valentine's celebration in Fort Lauderdale, where other romantic icons of the time, like romance novel cover model Fabio, Love Boat star Gavin MacLeod, and Dating Game host Jim Lange were all on hand to inaugurate the cruise line's newest ship.

"Men were running around dressed like Cupid shooting pretend arrows," recalls McDermott. Also onboard: 50 couples who had connected on Match but had never met in person, there to be collectively introduced for the first time in what was billed as the World's Largest Floating First Date.

"Some people, the chemistry, you just saw the love happen, and with some of them, there was zip," recalls McDermott. "In those three days, some of them started getting interested in other people."

The site also began to actively expand abroad, and found that just as You've Got Mail helped normalize online dating in the U.S., another contemporary comedy paved the way in much of Europe.

"By far, the most fascinating thing that we figured out, and we figured out totally by accident, is that in countries where there was syndication of the show Sex and the City, we had immediate adoption of our model," says Joe Cohen, who ran the site's international operations from 2001 through 2006. "We literally got a map of where Sex and the City was in syndication, and that was one of our criteria for where we launched."

The show didn't mention Match, but Cohen believes it helped pave the way for American-style dating in the countries where it aired, making online coupling services more relatable. Even in London, where he was based, Cohen said people were initially skeptical of the service when he first started at the company, though its popularity soon grew.

"They literally said, that's like prostitution," he says. "They looked at me like the face people get when they smell a fart."

In the U.S., meanwhile, the number of dating sites expanded rapidly in the 2000s, with ads promoting newer sites like eHarmony, PlentyOfFish, and Zoosk becoming common sights online and off. Niche dating sites also took off, with services from ChristianMingle to Veggie Date targeting specific interests, religions, and racial groups looking to find likeminded people, and by 2013, the Pew Research Center reported that about 40% of online dating customers had used such a specialized service.

Love In The Time Of Tinder

Yagan, who's now the head of the Match Group, which includes IAC's dating sites and a few other online properties, entered the field in 2004 as a cofounder of OkCupid. That site, which eschewed paid memberships in favor of advertising and paired users based on their responses to quirky questions, was widely hailed as a younger, hipper alternative to Match and other old-guard dating sites like eHarmony.

"Match.com had lost some of its coolness—it was not the cool site to be on," recalls Gerngross, who returned for a bit to online dating after a divorce in the early 2000s. "It had gotten a bit middle-of-the-road."

While at OkCupid, Yagan and his cofounders took frequent potshots at Match, still the industry leader, in media appearances. "Overthrowing Match.com is our job,"he told the Harvard student newspaper in 2009, in a story published on Valentine's Day. In 2011, IAC acquired OKCupid for about $50 million, and in 2012, the company appointed Yagan to head the entire Match division.

"You poke fun as competitors, of course, and you get in, and you realize there's a lot more happening under the surface than you probably realized as an outsider," Yagan now says of the erstwhile rivalry.

Part of Match's strength lies in its paid membership model, which filters for users who are serious about finding companionship, he says.

"The point of paying isn't just the money—it's the signal of intent," he says. "It's important to me that Match still gets that signal from its user, so that we can provide that high-intent community."

Still, Yagan points out that the service has been updated under his watch, making the jump from desktop to mobile.

"When I took over at Match, we didn't have an iPhone app, and that was in 2012," he says.

As of last year, the site has an updated iOS app with swipe-to-like and proximity-based features similar to Tinder—another Match Group property that's arguably upstaged both Match and OkCupid in recent years. (Between launching in 2012 and 2014, Tinder signed up about 50 million users, according to a source in thisNew York Times story.)

This April, almost exactly two decades after users first logged on to Match with their dial-up modems and Netscape Navigator, the company released an Apple Watch app that lets users review and message their matches with the tap of a wrist.

By now, more than 125 million people have registered for Match, including 20 million who've used it through their mobile devices, the company says.

"It was time for an online dating service that could keep things clean enough and be nimble enough, we'd call it today, to scale," says Wayman, the former Match editor. "Nobody was using that term—but we scaled."