Does your boss even appreciate how much time you're spending in meetings every week? Probably not.

Even though it might be easy to count the hours by looking at your Outlook or Google calendar, until recently, it was hard for organizations to compute those kinds of numbers on a companywide basis. In many companies, that's led to a situation where managers invite employees to an ever-increasing set of recurring status updates, brainstorming sessions, and weekly check-ins. Kick-offs and roundtables; team meetings and all-hands meetings.

Rank-and-file cubicle dwellers might privately gripe they're spending too much time in meetings they don't really need to attend, and higher-ups might silently wonder why there are always so many faces around the conference table, but workers are naturally loathe to ask their bosses to stop bringing them to meetings. Managers, meanwhile, are wary of marginalizing their staff by taking them off the invite list.

"It's like everybody's trapped," says Ryan Fuller, the CEO and cofounder of "people analytics" startup VoloMetrix. "I think most companies are in a vicious cycle of this getting worse and worse."

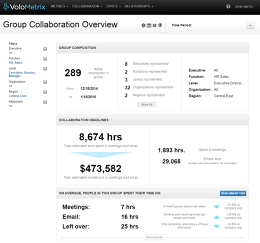

Fuller believes data can change all that, and solve a few other workplace headaches too. His Seattle-based company builds software that mines information like employees' Outlook calendar entries, email headers, and instant messenger logs to help companies figure out how their employees are spending their time—how much time salespeople are spending with customers, which divisions of the company are staying in touch by email, and how much time employees are spending in meetings. With those numbers, Fuller says companies can make changes, like bridging connections between loosely connected divisions that could stand to talk more, or setting goals for time spent in meetings that give everyone license to revisit those invite lists.

VoloMetrix, founded in 2011, is part of a wave of startups aiming to let employers track new measures of employee behavior, happiness, and engagement as readily as they monitor sales numbers and online traffic. And much like companies tracking consumer behavior on the web, they're taking advantage of new number-crunching and data storage capabilities—"the processing power really wouldn't have been there a couple of years back," Fuller says—and navigating uncharted legal and ethical territory regarding expectations of privacy.

New Territories

"What we spent the first couple of years building was a very robust, enterprise-grade security infrastructure, as well as educating ourselves on the all the legal issues, all the privacy issues, all the different things out there," says Fuller. "We found that most companies don't have a policy that applies to what we do, so we have to help them invent it."

For instance, the tool doesn't delve into the bodies of individual messages or IMs: only the header information—the metadata—is captured, he says.

"We never go below the line of headers—to, from, subject line, date, time," says Fuller. "We don't touch message content or attachments or anything like that."

And the stats are anonymized and generally only presented to employers as aggregate information about groups of employees, not as reports on individual worker behavior, he says.

"We default to 100% anonymous, group-level data with no PII included for company employees," the company says in its privacy policy, using a common abbreviation for personally identifiable information. "No business user can remove the anonymity."

Individual employees can also see how they stack up against the company at large and company goals, helping them work to adjust time spent sending emails, attending meetings, or working with customers.

Analytics For Face Time Too

A Boston-based startup called Sociometric Solutions goes even further, looking beyond email records and meeting schedules to actually monitor how employees are interacting in face-to-face conversations using wearable electronic badges that track who's talking to whom. The badges are also capable of registering the tones of voice and body language workers are using.

The company's been able to help its clients find productivity-boosting patterns, says cofounder and CEO Ben Waber. One financial-services firm learned that back-office employees benefitted from interacting more frequently with their customer-facing colleagues, and another client, a pro sports team, got insights into how, and even where in the stadium, their top salespeople converted game-going fans into season ticket holders.

"If you spend 5% more of your time talking to customers in this part of the arena, here's how much more money you'll make," Waber says they were able to advise sales staff.

The company makes sure to get individual workers' consent and takes steps to protect privacy, says Waber.

"We don't record what people are saying," he says. "We don't count how many times you go to the bathroom."

And, as with VoloMetrix, data are only presented in aggregate, Waber says. Companies can see how members of different teams interact, or how the set of top performers in each group behaves differently from others, but only individual employees get access to their own individual data.

Waber has previously said the company even allows opting-out employees to wear dummy badges with no actual sensors, so their bosses don't know they've chosen not to participate.

But tools exist that allow companies to do more personalized monitoring, now that cloud-based systems have largely eliminated the storage costs and IT department headaches involved in storing and analyzing employee data in arbitrary detail.

When Workers Don't Know They're Being Watched

One tool, called ActivTrak, lets employers automatically log how long each of their workers spends in particular applications and visiting individual websites. It doesn't log individual keystrokes, but it can be configured to take regular screenshots throughout the day, or when employees trigger alerts by visiting certain sites, says Herb Axilrod, president of Dallas-based Birch Grove Software, ActivTrak's maker.

"You can begin recording screenshots of a certain window as long as that window is active," he says. "It doesn't record text of email messages or chat sessions, although that can be captured via screenshots if the alarm is set up to do that."

Axilrod says the company encourages customers to let their staff know they're being monitored, but it's ultimately up to individual employers whether they choose to do so. ActivTrak's frequently asked questions page explains users won't be able to detect when the software's installed, and advises employers looking to keep that fact a secret, not to accidentally leave behind any clues.

"You will probably not want to use their browser to download and install the Agent, as that would leave a browser history record that you might forget to delete," the page warns.

Installing the software and monitoring computer usage without employees' knowledge is generally perfectly legal in the U.S., though European law is stricter, says Axilrod.

Legislative gridlock has essentially prevented Congress from tackling the issue, explains Corey Ciocchetti, an associate professor of business ethics and legal studies at the University of Denver's Daniels College of Business, who's written about workplace monitoring.

Even as far back as 2007, a widely cited survey by the American Management Association and the ePolicy Institute found about two-thirds of employers polled monitored their workers' web use, and 45% said they monitored how employees were spending their time on company computers, the content they viewed, or the actual keystrokes they entered. As the organizations prepare to conduct a new survey this year, legal experts have suggested that the numbers have likely only increased as technology has spread throughout the workplace since 2007—a time when, according to the same survey, only 10% of companies reported monitoring how their brands were being discussed on social media.

Workers often don't realize how much existing technology—from Internet monitoring tools to access card systems that can track their comings and goings—lets their employers track their activities, says Ciocchetti.

"I think at a minimum, you should have to notify employees what you're doing," he says. "I would like to know in plain English, not legalese, how are you monitoring me, and give me that information when I'm hired."

One risk is that unscrupulous bosses can use all that data to get away with firing an employee for legally dubious reasons by trolling for otherwise unnoticed policy violations, like an off-color joke sent through company email or late arrivals logged by a keycard system. "It's the way that they fire you, and nobody bats an eyelash about it," Ciocchetti says. "It lets them obfuscate their bad intentions."

At least for well-intentioned companies, though, ethical concerns could lead to self-imposed curbs on employee surveillance and sensible disclosure policies, he says.

And the sense of surveillance can easily damage morale. "If your employees are happier, they're more efficient and more productive," he says.

Some research suggests that excessive monitoring can itself curb productivity and innovation, says Karen Levy, a fellow at New York University's Information Law Institute and the Data & Society Research Institute.

"We don't know exactly what that mechanism is," she says, though one influential paper she cites by Harvard Business School assistant professor Ethan Bernstein suggests overly aggressive monitoring and measurement leads workers to hide or simply refrain from any deviations from established practice—even those that benefit the company.

How Do You Look At All That Data?

Beyond the ethical and psychological questions, how does a company and its employees begin to make sense of the piles of data being collected in the office? A recent project by Microsoft's Envisioning group and The Office for Creative Research, a New York data visualization consultancy, explored some of the visual and interface possibilities for examining big data sets, using custom visualization software intended to be as easy as Excel.

"We think there's a really massive opportunity to have new sets of tools that allow you to interact with these massive datasets," says Harald Becker, a Microsoft Envisioning senior design strategist.

And the dataset used for the project, called Convene, was one that would be familiar to Microsoft employees: an anonymized slice of Microsoft's internal Outlook calendar database, which shows meeting patterns across tens of thousands of employees and contractors at the company's Redmond office.

The Convene team built interactive network visualizations that tracked what OCR cofounder Jer Thorp calls meeting "breadth"—the number of distinct teams represented in meetings—and "depth," essentially the range of rank of employee in particular meetings. The visualizations are displayed on enormous touch screens, using gestures reminiscent of the computers in Steven Spielberg's Minority Report.

"One of the things that Microsoft is really trying to do is increase connectivity across departments," Thorp says. "I think all organizations in general are moving away from being these siloed beasts to being these networked entities."

In the future, the tool could be used to help Microsoft or other organizations see how their employees are interacting, or to help individual users track their own meeting schedules—kind of a FitBit-style quantified self tool to help workers optimize the time they spend in meetings, says Thorp.

"If you had a running app, you might be trying to ramp up to a marathon," he says. "If you have a meeting app, you're trying to ramp down."