In 2013, a pair of private investigators in the Bay Area embarked on a fairly run-of-the-mill case surrounding poached employees. But according to a federal indictment unsealed in February, their tactics sounded less like a California noir and something more like sci-fi: To spy on the clients' adversaries, prosecutors say, they hired a pair of hackers.

Nathan Moser and Peter Siragusa were working on behalf of Internet marketing company ViSalus to investigate a competitor, which ViSalus had sued for poaching some of its former employees. Next, the government alleges, Moser and Siragusa—a retired, 29-year veteran of the San Francisco police department—recruited two hackers to break into the email and Skype accounts of the competing firm. To cover their tracks, they communicated by leaving messages in the draft folder of the Gmail account "krowten.a.lortnoc"—"control a network" in reverse, according to the indictment.

Federal prosecutors did not specify how the defendants found their hackers, but an email address apparently belonging to one of the hackers, Sumit Gupta of Jabalpur, India, was also used last year on the freelancer message board WorkingBase by someone seeking software that could compromise computers running Windows and Microsoft Office. The poster, who was offering $250 to $750, wrote, "Code should be FUD," meaning fully undetectable, "and fully working. Looking a cheap cost."

The California case sheds light on a burgeoning cybercrime market, where freelance hackers, both on public forums and in black markets, cater to everyone from cheating students and jealous boyfriends to law firms and executives, according to Jeffrey Carr, president of Seattle-based security firm Taia Global. He calls the industry "espionage as a service."

While it is difficult to verify the legitimacy or the quality of the hacker postings on a half-dozen online exchanges that Fast Company examined, some sites boast eBay-like feedback mechanisms that let users vouch for reliable sellers and warn each other of scams. Carr describes a range of expertise, from amateur teenagers wielding off-the-shelf spyware who may charge up to $300 for a single operation, to sophisticated industrial espionage services that make tens of thousands of dollars or more smuggling intellectual property across international lines. "The threat landscape is very complex," he says. "A hacker group will sell to whoever wants to pay."

At Hackers List, for instance, hackers bid on projects in a manner similar to other contract-work marketplaces like Elance. Those in the market for hackers can post jobs for free, or pay extra to have their listings displayed more prominently. Hackers generally pay a $3 fee to bid on projects, and users are also charged for sending messages. The site provides an escrow mechanism to ensure vendors get paid only when the hacking's done.

While Hackers List says it's intended only for "legal and ethical use" like recovering lost passwords, it boasts about a dozen job listings a day, in some cases to anyone capable of hacking into private websites, social media accounts, and online games.

In a report released in March, Europol, the European Union's law enforcement arm, predicts online networking sites and anonymous cash-transfer mechanisms like cryptocurrencies will continue to contribute to the growth of "crime as a service" and to criminals who "work on a freelance basis . . . facilitated by social networking online with its ability to provide a relatively secure environment to easily and anonymously communicate."

The environment isn't always secure. Earlier this month, one security sleuth unmasked the apparent owner of Hackers List as Charles Tendell, a Denver-based security expert. Soon after, Stanford legal scholar Jonathan Mayer crawled the site's data, revealing the identities of thousands of the site's visitors and their requests for hacks.

Mayer found only 21 satisfied requests, including "i need hack account facebook of my girlfriend," completed for $90 in January, "need access to a g mail account," finished for $350 in February, and "I need [a database hacked] because I need it for doxing," done for $350 in April. A majority of requests on the service involve compromising Facebook (expressly referenced in 23% of projects) and Google (14%), and are sparked by a business dispute, jilted romance, or the desire to artificially improve grades, with targets including the University of California, UConn, and the City College of New York.

While most requests "are unsophisticated and unlawful, very few deals are actually struck, and most completed projects appear to be criminal," Mayer wrote on his blog, the requests were a "fair cross-section of the hacks that ordinary Internet users might seek out." Still, he wrote, Hackers List "certainly isn't representative of the market for high-end, bespoke attacks."

Whatever the software or however expert the hackers, the basic methods of intrusion are often the same: the age-old technique of tricking a target into installing malware by opening an email attachment or a malicious website. "It's like we still use gasoline in gasoline-driven engines," says Carr, "'cause it just works."

A Silk Road For Hackers

On the message board site HackForums.net, users openly post ads offering to hack into computers and online accounts, knock servers offline with denial-of-service attacks, and track down strangers' personal information, all for a fee. Hackers are ranked through a rating system, and high-reputation users even offer "middleman" services, holding cryptocurrency payments in escrow until sellers deliver what they've promised.

"I will Hunt someone for you and get you all the informations of the person. ( emails, IMs, Social accounts, location, phone number, Home address etc)," says one post on the site, which is registered in the Cayman Islands. "I will hack someone for you and get you all the files, key logs, webcam videos, anything from his system. on your need, i can transfer them on your rat/botnet, so you can play with him." A RAT is a remote administration trojan: a piece of software that, once surreptitiously installed on your target's computer, tablet, or phone, allows you to read files, intercept keystrokes, and generally take control of the machine's operations.

One forum user named Hax0r818 said in a Skype chat that his service, which mentors neophyte RAT users, has had about 300 customers in roughly a year. "I just help them get started because R.A.T.s are not for hacking they were made for parents to check what there children are looking on the net," he wrote. "I dont aks them anything I dont because I don't care I just give them a warning that using R.A.T.s for iligal purpeses can get them to jail and I let them agree to my Terms."

Hax0r818, who would say only that he is under 21 and based in Australia, charges $5 a month in exchange for training RAT novices in using the tools and providing a testbed virtual machine for them to practice on.

In addition to websites accessible through the web, a dozen deep web markets—with names like Hell, Agora, Outlaw, and Nucleus, and only reachable through the Tor browser—offer menus of RATs and other hacking software and services, with transactions conducted in Bitcoin.

"Hacking and social engineering is my business since i was 16 years old, never had a real job so i had the time to get really good at hacking and i made a good amount of money last +-20 years," writes the owner of Hacker for Hire, a dark web site that charges 200 euros for small jobs and up to 500 euros for larger ones, including "ruining people, espionage, website hacking.""I have worked for other people before, now im also offering my services for everyone with enough cash here."

Typical prices for RATs—with names like darkcomet, cybergate, predator pain, and Dark DDoser—range from $20 to $50, according to a December Dell SecureWorks report. This represents a significant drop from the previous year, when the tools typically sold for between $50 and $250. (The price drop may have resulted from the recent leak of some RATs source code.) The price for hacking into a website has also dropped, from a high of $300 to $200, according to the Dell report.

One RAT-making group called Blackshades took in more than $350,000 over four years selling a $40 RAT on hacker forums and its own website to thousands of buyers around the world, according to a federal indictment unsealed last May in New York. Customers had used the software to steal financial information and spy on unsuspecting victims through their webcams, officials said.

"The RAT is inexpensive and simple to use, but its capabilities are sophisticated and its invasiveness breathtaking," Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara said at the time. His investigation, part of an "unprecedented" and ongoing global effort, has so far resulted in more than 90 arrests.

Big Business And Big Crime

Hacking software, which can cost up to $3,000 and more, isn't itself illegal, and can be used for benign tasks like remotely administering servers and monitoring corporate computers. But in practice, these software toolkits and related services are often used for fraud, denial-of-service attacks, or network intrusion.

"If someone is gaining unauthorized access to another computer system, anything digital, that is against the law, that is criminal," says Jonathan Rajewski, a computer forensic examiner and assistant professor at Vermont's Champlain College.

Hacker marketplaces, meanwhile, exist "in legal limbo," according to Mayer, the Stanford law lecturer. While websites are generally not liable for user misdeeds, there is an exception for federal criminal offenses, including violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which governs hacking. That leaves the operators of these markets open to possible accomplice or conspiracy charges, which could land them in prison.

The operator of the Silk Road, where hackers advertised alongside drug sellers, was convicted on hacking conspiracy charges, along with six other counts. A newer dark net marketplace called TheRealDeal Market, also accessible through the anonymized Tor network, focuses specifically on exploit code, though the terms of service say the site allows the sale of anything except child pornography, human trafficking, or "services which involve murder."

Last week, the U.S. Commerce Department published a proposal that would require anyone selling unpublished "zero-day" exploits internationally to have a license, classifying intrusion software, like other "dual use" items, as potential weapons. The number of zero-day exploits discovered in the wild hit an all-time high last year of 24, according to a recent Symantec report.

The new law could help law enforcement fight hacker black markets, but it would also hinder a number of companies that openly sell intrusion software and software exploits. The French security firm Vupen, which bills itself as a provider of "offensive cyber security," charges clients—including the NSA—up to $100,000 per year for access to techniques letting them compromise widely used software, from Microsoft Word to popular web browsers and Apple's iOS. The Italian company Hacking Team has sold RATs to the FBI. Other firms that buy and sell exploits include Netragard and Endgame, as well as larger defense contractors like Northrop Grumman and Raytheon.

Recent estimates have predicted industrial espionage and other digital crime costs companies hundreds of billions of dollars per year. A new study by the Ponemon Institute found that the average cost of a compromised record for a corporate hacking victim rose to $154 in 2014, up 8 percent over the previous year.

Selling To The Highest Bidder

To Carr, the security researcher, the consumer hacking-for-hire market is only the tip of the iceberg. Now, more sophisticated hacker groups are offering their services to wealthy overseas businesses and governments interested in buying "on demand" hacking. An entrepreneur or a C-level executive might hire a hacker to gain an edge over competitors, for instance, or to "hack back" against cyber intruders, a practice that Sony reportedly employed in its effort to fight websites hosting the company's leaked data.

With so much recent focus on allegations of hacking by government agencies, Carr thinks threats from sophisticated commercial operations have been somewhat overlooked.

"We've completely missed until recently the espionage-as-a-service game, and most likely we've confused these guys with actual government intelligence agencies or government military operations," he said.

Hacker groups will generally find work by exploiting connections to unscrupulous companies, either striking deals to obtain particular data or by stealing valuable information themselves and selling it to the highest bidder they can find, according to a white paper recently released by Carr's firm, Taia Global.

Carr pointed to the case of a Chinese businessman named Su Bin, who was arrested in Canada last year on charges he worked with two unidentified hackers to steal and sell trade secrets about the F-35 and other military aircraft from U.S. defense contractors. In one email, one of Bin's alleged accomplices attempts to buy an undetectable copy of "the Poisonivy Program," a well-known RAT tool that is available in encrypted form, from a HackForums.net seller for just a few dollars.

But in spite of widespread reports about hackers stealing secrets for the Chinese government, Bin, who lived and worked in Canada, seemed more motivated by financial rather than nationalistic interests. "These buyers weren't necessarily Chinese companies," according to the Taia Global publication. "One email from Bin . . . indicated that he was unhappy with how cheap one Chinese company's offer was and that he would look for other buyers."

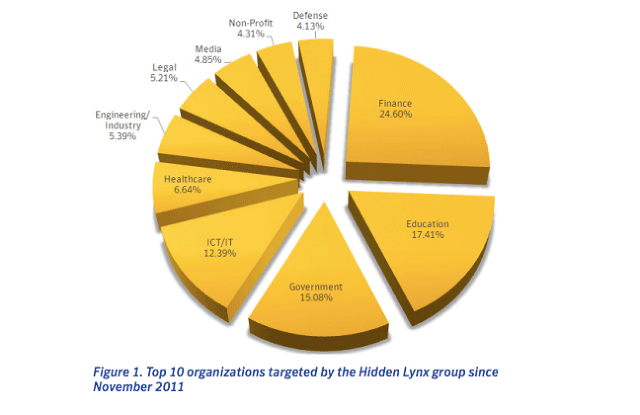

One sophisticated espionage-focused group, dubbed Hidden Lynx by security firm Symantec, used two pieces of custom malware to penetrate hundreds of organizations around the world. Based on the variety of targets the group has targeted, Symantec believes it to be an "adaptable and determined" hacker-for-hire organization.

"We believe they're specifically tasked with going after information and then passing that information to the clients that want it," said Symantec senior threat analyst Stephen Doherty, one of the authors of the paper, who says his firm has been following dozens of similar groups. "Symantec is tracking over 70 groups from all around the world that fit into the various buckets of those involved in direct espionage, those involved in cybercrime, those maybe doing a bit of both," he said.

Hidden Lynx, which Symantec says employs between 50 and 100 hackers operating mostly out of China, breached the servers of security firm Bit9 in 2012, making off with security certificates used to digitally sign software Bit9 has certified as safe. The hackers then gained access to computers belonging to political, defense, and financial organizations in the Boston and Washington areas by penetrating web servers likely to be visited by employees of target companies and using them to distribute malware, some of it signed with the stolen Bit9 credentials.

Playing Defense (And Offense)

As hacker groups have become more sophisticated, defensive efforts by international law enforcement and private security groups have grown more coordinated, with the ultimate goal of making such attacks that much less worthwhile, said Doherty. Last year, the tide against Hidden Lynx changed: A coordinated effort by a number of security vendors helped develop better protections against the malware used by the group, Symantec says. "All our indications are that the activity involved with this group has very much gone underground," he said.

"I think you're seeing a breakdown of the kind of silos where everyone's fixing their own, or looking after their own client base," said Doherty. Previously, he said, "whether it's an [antivirus] company, or whether it's a bank, they all would have very much worked close to home, but now we're seeing a much broader effort. There's much more visibility into what's going on."

Doherty said people and companies hoping to defend against these kinds of attacks should take traditional online security precautions: Keep up to date with software upgrades and security patches, watch for unusual network activity, and take special care to lock down systems known to store valuable company secrets.

Companies should also take careful stock of which third-party vendors have access to their sensitive information, said Carr. "You also need to do due diligence on all of your supply chain," he said. "You have to be aware of who you're sharing your data with: Just because they're your vendor doesn't mean you can trust them."

One tactic Carr advises against: "hacking back," the risky and legally murky technique of retaliating against the networks of criminals who infiltrate corporate networks.

"That's always a bad idea," he said. "It's like that old saying, never pick a fight with a stranger—you don't know who you're throwing a punch at. It could be a commando."